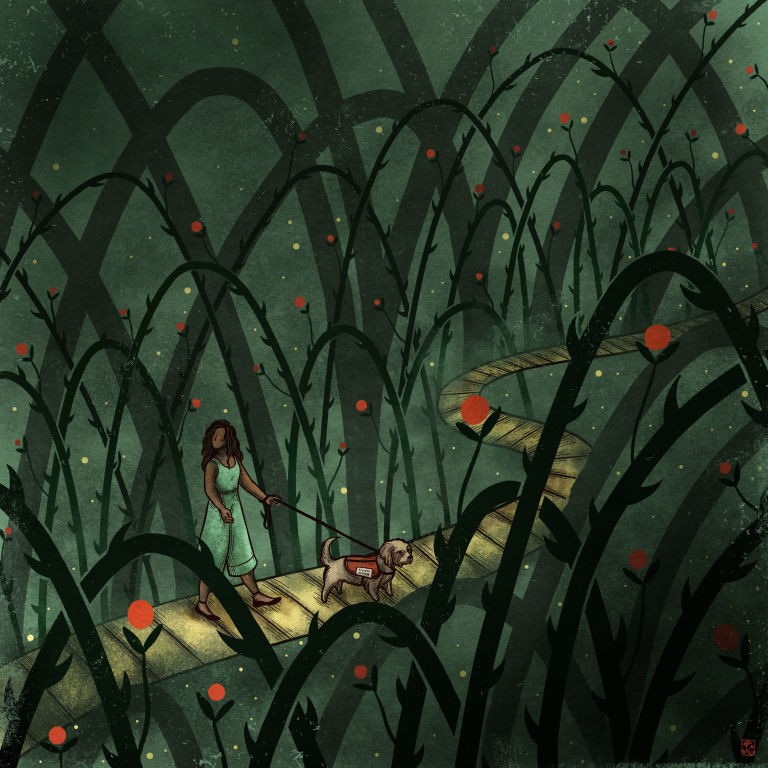

I stood outside a sprawling casino resort, shivering as the temperature dropped below 50 degrees. I watched my breath escape my body and wade into the night air, and my service dog nuzzled my leg with his snout. Giant was the peacekeeper in the middle of the hellfire this night had become, my reminder that it would all be okay.

I was hopping back and forth to stay warm when my fiancé approached me. “I went to the front desk and ordered a cab. It will be here in 15 to 20 minutes,” he said.

The casino was in the middle of nowhere, just off a country highway. There were no Lyfts around and no cabs immediately available for pickup. We had to wait outside, in the cold, because going inside just wasn’t safe.

***

Disabled is a complex term to use when you look like me: healthy, strong, and able-bodied. But I do have a disability — post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD — and I crave the freedom to self-identify as I navigate the label-obsessed world in which we live. I don’t *want* to have a disability; in fact, I don’t think any person with a disability does. But I don’t want to be expected to pretend it doesn’t exist. Often, it feels as if I am being gaslighted by the world, pressured to claim good health, push myself beyond my limits, and pretend that my life hasn’t been saved by a drug cocktail that my doctors have carefully curated over the past two years.

That had been exactly the case earlier that night, leading up to our chilly wait for a cab. My fiancé and I had spent the day in a nearby town, hiking and going to our favorite local restaurant. We wanted to end the evening by visiting the casino in the town over. We used to go to the casino fairly regularly, until we both decided that weekends playing Blackjack and buying diluted cocktails at inflated prices wouldn’t help us save for the home and future we wanted together. That night, however, we embraced spontaneity.

I walked into the lobby with my service dog and was promptly told that although my fiancé could go in, I’d have to step to the side and wait for a manager to come verify that I actually needed a service animal. It was a little annoying, sure, but I brushed it off and suggested my fiancé go get some cocktails; we agreed to meet up when I was finished speaking with the security manager. That turned out to be wishful thinking. What unfolded was a prolonged interrogation.

__Why do you have a service animal, ma’am?__

“I have PTSD,” I willingly explained.

__What is the animal trained to do?__

I cooperated by explaining the four tasks he can perform.

__A lot of people come in here faking service animals. We don’t allow emotional-support animals.__

“I can assure you that Giant can perform specified tasks; he has been trained, and I can answer whatever questions you need to know about his skill set. Also, he is not an emotional-support animal,” I said. “Those are two different things, and it is demeaning to insinuate he must be an ESA, because I have PTSD. Psychiatric-service animals are common and valid.”

__Look at him; he’s not even doing anything right now!__

This is when my blood started boiling. “Even seeing-eye dogs get breaks when their handler isn’t moving or in need of immediate assistance,” I responded curtly.

Clearly, the casino staff is unaware of the wide array of service animals and the services they must perform for handlers with invisible illnesses in case of emergency. “Does someone have to have a seizure, or pass out, or have a dissociative attack on command for you to honor their disability?” I shot back.

At one point, the manager on duty told me I was too pretty to have a disability — and that my dog was too pretty to be a service animal.

“My explaining his tasks should be enough, but I’m happy to provide you with additional documentation if necessary,” I pleaded. I just wanted to enjoy a night out with my fiancé.

Never mind that I offered to show a copy of a doctor’s note on official letterhead detailing the services my dog provides. Never mind that I was willing to relinquish my right to medical privacy and show them the medications I have to keep on me at all times in case of emergency. There was no reasoning with security staff; the answer was a strict NO, and I had to leave the premises.

***

Disability does not discriminate, and neither does PTSD. There are survivors of physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, combat, and serious injury, and/or survivors of experiences that involved actual or threatened death. Much like other illnesses and disabilities, PTSD has nothing to do with how pretty I am or anyone else is. The disorder — and the havoc it can wreak on your life — is both blind and relentless.

So that’s how I ended up outside. Shivering in the cold and hopping from one foot to the other as I awaited a cab. Giant continued nuzzling my leg; occasionally, if he sensed my anxiety rising to a level that could trigger a panic attack, he’d offer a few generous licks. Tactile stimulation, experts call it. It is one of the four tasks that he has learned to do on command. For Giant, licking me isn’t simply a show of affection or a desire for sodium; it’s a way to disrupt my thought process when I start trembling, feeling faint, and am unable to bring myself back down.

“Let’s just go back in,” my well-meaning fiancé pleaded. “You’re cold, and we still have to wait a while.”

“No, I simply don’t feel comfortable. Security told me I have to leave, and I don’t want things to escalate,” I explained. “Black people have been shot for less.”

He looked at me with compassion, a look that said, I can’t fully empathize, but I’m trying to.

I have to navigate the world a bit differently than my white fiancé. He’s a quick learner and incredibly socially aware, but sometimes he doesn’t realize that there are small conveniences — like taking shelter in a warm lobby — that seem out of reach for a woman of color like me.

And, sure enough, as the cab dispatcher updated us that the wait for a ride would be at least another twenty minutes, the local police showed up. Not one patrol car, but two. *I was being apprehended for being myself.*

It was at this moment that I felt less than human. I have long known that I’m a triple minority: black, female, and clinically disabled. But I’ve never witnessed such a sickening display of power. The casino security guards were punishing me for expressing my civil rights. Not only had they refused my entrance, but they were now devaluing my personhood to the extent that they called the police on me.

I stood in fear, awaiting the officers’ approach. Once they reached me, they asked us to hand over our IDs. We both did so willingly, and before they walked away, I had a question. “May I ask what you’re running our IDs for, officers?” I was apprehensive but well-versed in my rights.

“We’re just going to run your IDs, check for warrants, things like that. The casino called us, and so we want to be sure that there isn’t a warrant for your arrest,” he explained. “You would be surprised how we catch bad guys sometimes.”

I quietly responded that I understood, having two uncles in law enforcement with plenty of tales of criminals who evaded justice for far too long. They walked away, and I stared at my fiancé helplessly. It was just him, me, and Giant … standing in a field near the casino. My fiancé silently reached out and put his arm around me, cradling me as I shook with not only chills, but fear as well.

Within minutes, both officers returned with our IDs. They explained that we were good to go, and I breathed a sigh of relief. I was well aware that my fiancé simply had an old speeding ticket on his record and I just had some parking violations, but I was still anxious that they’d find some reason to push this night from bad to worse.

Luckily, something good came out of that interaction: absolution. The officers acknowledged we had done nothing wrong, quickly said a polite farewell, and sped off into the distance.

So there we were. I was humiliated. My fiancé, empathetic. My service dog, at the ready and on watch for distress. The three of us stood there, cold, frustrated, and eager to go home. After almost an hour, a rusty tan van pulled up in front of us, and the driver apologized for the delay. I sat in the back seat, where I had to observe our driver’s large, pimply rear end hanging halfway out of his shorts and enveloping the entirety of the seat. It was a long, nine-minute drive back to our car; we had parked it at the restaurant where we’d eaten dinner. When we arrived there, the three of us hopped out and paid the fare: $57, plus tip. A large price to pay for a quick ride down abandoned country roads, but definitely not the biggest price I had paid that night.

*Alexis Dent is an essayist and poet whose debut collection, (1), is available now.*

1) (https://www.amazon.com/Everything-Left-Behind-Alexis-Dent/dp/1945796677/)