During my first year in college, I was silent. I never skipped class and read every page assigned to me, but I didn’t speak, even though I was in a program called the Great Conversation. I was too afraid of saying something wrong. This period of silence neatly coincided with three years of starving — a task that focused all my energies on physical hunger in order to ignore intellectual (and sexual) desires that frightened me.

I declared a religion major as a sophomore and took a class from Barbara, a young theologian. Although I’d grown up in the Protestant church and was the child of a pastor, I didn’t have a clue what feminist theology was about, but the class fit with my schedule, and I’m so glad it did. My mind was split open by a range of new thinkers and writers and by the quality of Barbara’s questions. I finally had something to say and the energy to say it. I started talking, and then I couldn’t stop. I started eating, and I felt better. I was a frequent visitor during Barbara’s office hours, a rocket of words. She listened, calmly responded, her peaceful exterior a perfect counterpoint to my manic ramblings, and helped me organize my erratic thoughts.

I loved what she saw in me, which was a range of abilities I had never seen in myself. The discovery of the quality of my interior life was a love affair I have never stopped pursuing, and it never gets old.

> I loved what she saw in me, which was a range of abilities I had never seen in myself.

I spent my junior year in Dublin, and that spring Barbara sent me an email announcing the birth of her daughter, Maggie. I hadn’t stopped to think that my favorite professor had a life of her own that was progressing simultaneously to mine, but in a very different way. I quickly typed a note of congratulations and wandered to a nearby coffee shop, feeling strangely weepy. I realized that I loved Barbara for the ways in which she reflected an ideal version of who I wanted to be. But what did I know about her life?

Gradually, I learned more. During my senior year, when Barbara was my thesis adviser, I was Maggie’s babysitter. When she cried as her mother left to teach her class, Barbara’s voice trembled as she said “I love you” to her little girl. I sang her lullabies, fed her tiny cheese cubes and hot milk. That year, when I was awarded a Fulbright scholarship, I sprinted to Barbara’s office in the basement of the school chapel. We whooped loudly, our voices echoing scandalously out of tune with the choir practicing upstairs.

In the years after I completed my program I visited Barbara in Palo Alto when she and her husband took teaching jobs at Stanford. I watched Maggie fall in love with sharks and Disney and, later, Dance Dance Revolution. I met the pet bunny and the black Labrador. Barbara had a boy, and one afternoon when he was about six years old Barbara and I watched him shoot baskets at his school, blond hair falling in his eyes. Our relationship gradually deepened, but I was always conscious of a teacher-student dynamic. We were both a bit guarded, a rarity for me, but I wanted to impress her.

This changed fundamentally when I became a parent.

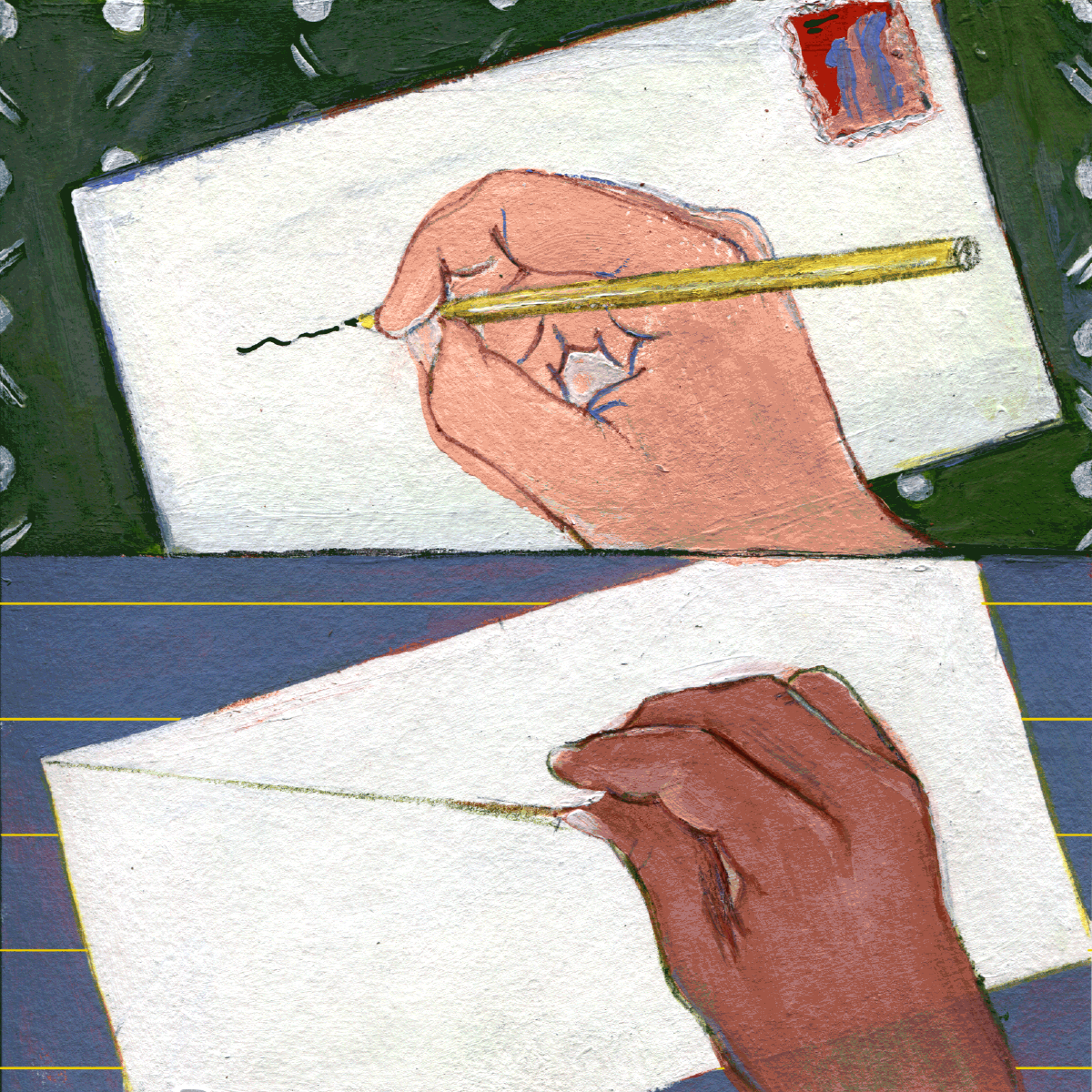

When I began writing about my son and my grief experience in a very public blog format, beavering away on essays long into the night, Barbara responded to each one. Her husband was worried, she wrote, that reading my posts and peering so deeply into another’s despair would upset her. “How does one negotiate the relationship between that which we know and that which we choose to tell?” she wondered. But, she went on, “reading for me is just sitting and listening and silently just being there.”When I had my son in March 2010, Barbara was one of the first to congratulate me. When my child was diagnosed with Tay-Sachs disease nine months later, a rare and always terminal illness with no treatment and no cure, she wrote me a letter — handwritten, on a white legal pad. For the next two and a half years, Barbara wrote me regular, sometimes weekly, letters, remarkable letters that are revealing, loving, and kind. Honest. Full of rage and searching.

She talked about the biblical Job and the way his friends were helpful to him in his great trials until they opened their mouths and tried to explain and rationalize his despair. “It all seems a terrible mistake, all this darkness,” she continued. “It must be; but here I’m in danger of starting to question, to rationalize, and that won’t help. Just know that I am thinking of you, sitting, and listening.” She promised to keep doing so, and she kept that promise.

> She promised to keep doing so, and she kept that promise.

Barbara’s letters were not just about my work and what was happening with my son but about her life as well. At first she worried about discussing the family vacation and the events of her daily life because she didn’t want to bore me, or hurt me, or make me feel rage. But I wanted to know, I wrote back. I wanted to peer into the life of someone whose family wasn’t falling apart, whose children weren’t dying, in part because I knew she didn’t pity me, she was walking with me, accompanying me in the age-old tradition of Ruth and Naomi, although we shared no familial tie.

She sent me book reviews, reports about her latest theological interests, the copy of an old check she had written me for babysitting services ($54.86, dated May 1996 — “We were so cheap!”), and one rollicking discussion from “a summer in full swing,” about what the nineteenth-century Protestant theologian John Calvin might say about luck. “Death won’t be the end,” she wrote, and I sensed in her a desire to believe this, even if she didn’t, not quite. Another was written with visibly shaky handwriting during a turbulent plane ride.

Through our back and forths, I began to realize that I hadn’t really known her at all — not until now — when she revealed more about herself than she ever had. Last summer she wrote, “I’m sending you lots of love and positive thoughts. Hope you feel it.” I did, and I do. Yes, we had decades of shared history behind us, but now we had truly gotten to know and love one another as women, thinkers, and mothers. Equals. This switch from youthful adoration to a more nuanced relationship included an element of loss. I was no longer young, foolishly believing that possibilities were endless. Our correspondence signaled an adult awareness of mortality, that death is always closer than we think.

> This switch from youthful adoration to a more nuanced relationship included an element of loss.

The last letter, written right before my son died when he was three, was the most personal and perhaps the most profound. I realized, reading it, that this exchange of ideas had altered us both, earned us one another’s trust in a new and radical way. She told me the story about Maggie’s birth, one that would never have been included in a mass email announcement. After Maggie was born, she was taken away, and a nurse arrived to take care of Barbara, to wash and comfort her. “Time seemed to stop,” she wrote, “and this moment in which the flow of time seemed to be completely suspended, my thought was this: this is a baptism, and this is the moment when I become a parent, this is the anointing.”

Barbara went on to say that she believed my experience of parenting a terminally ill child had made me a better person, not in a superficial, moralistic sense. “I think he’s made you better by opening up the great fire of your love,” she wrote, with his “small but magnificent existence.” I have never in my life read a more deeply comforting sentence, one that spoke to my grandest hopes, my deepest fears, and the only faith that remains to me, which is a belief in chaos. Our love had bloomed and deepened from a guarded mutual respect to a richer, deeper friendship.

Mentors are meant to usher those in their charge into fresh understanding, help them sort and filter new experiences, assist in the project of making sense out of the chaos that is human life, or at least doggedly ask questions that dig deeply toward those difficult and nuanced answers. It is a sacred relationship with ancient roots; I envision it as a mutual anointing, a loving recognition, a way of saying “I see you; I’m here.” Unlike Job’s friends, who want to sort and solve, mentors witness. They observe and accompany the darkest despair, the wildest sorrow, and the most unexpected joy. My mentor, who first taught me to love my mind, and later, when the life of the mind she had helped me develop was the only way to withstand and survive the thunderous days with my dying child, she wrote me letters that stood witness to my life, in all its wretchedness and joy, in all its terrible beauty. Nobody did it quite so well as she did.

_Emily Rapp Black is the author of_ (1), _and_ (2), _which was a_ New York Times _best-seller. Visit her at_ _ (3)_

1) (http://link.lennyletter.com/click/7114513.12/aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuYW1hem9uLmNvbS9ncC9wcm9kdWN0L0IwMDJUVlNGQ0kvcmVmPWFzX2xpX3RsP2llPVVURjgmdGFnPWxlbm55bGV0dGVyLTIwJmNhbXA9MTc4OSZjcmVhdGl2ZT05MzI1JmxpbmtDb2RlPWFzMiZjcmVhdGl2ZUFTSU49QjAwMlRWU0ZDSSZsaW5rSWQ9YzJjOTE4MTY5MTg0NzgzMDRiOTdjZDk1Nzc4Mzc0ODg/5672eded1aa312a87f2d6890B2fd66380)

2) (http://link.lennyletter.com/click/7114513.12/aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuYW1hem9uLmNvbS9ncC9wcm9kdWN0LzAxNDMxMjUxMDkvcmVmPWFzX2xpX3RsP2llPVVURjgmdGFnPWxlbm55bGV0dGVyLTIwJmNhbXA9MTc4OSZjcmVhdGl2ZT05MzI1JmxpbmtDb2RlPWFzMiZjcmVhdGl2ZUFTSU49MDE0MzEyNTEwOSZsaW5rSWQ9YjRlNmEyNDlkNDMyZjhiZjU4ZTdiZGZkN2M2NDRiNjk/5672eded1aa312a87f2d6890B368ce7c4)

3) (http://link.lennyletter.com/click/7114513.12/aHR0cDovL3d3dy5lbWlseXJhcHBibGFjay5jb20/5672eded1aa312a87f2d6890Bf9f12685)