*“The curse cannot be broken. Not even prayer can get rid of the JuJu.”*

*—Rose, a sex-trafficking victim*

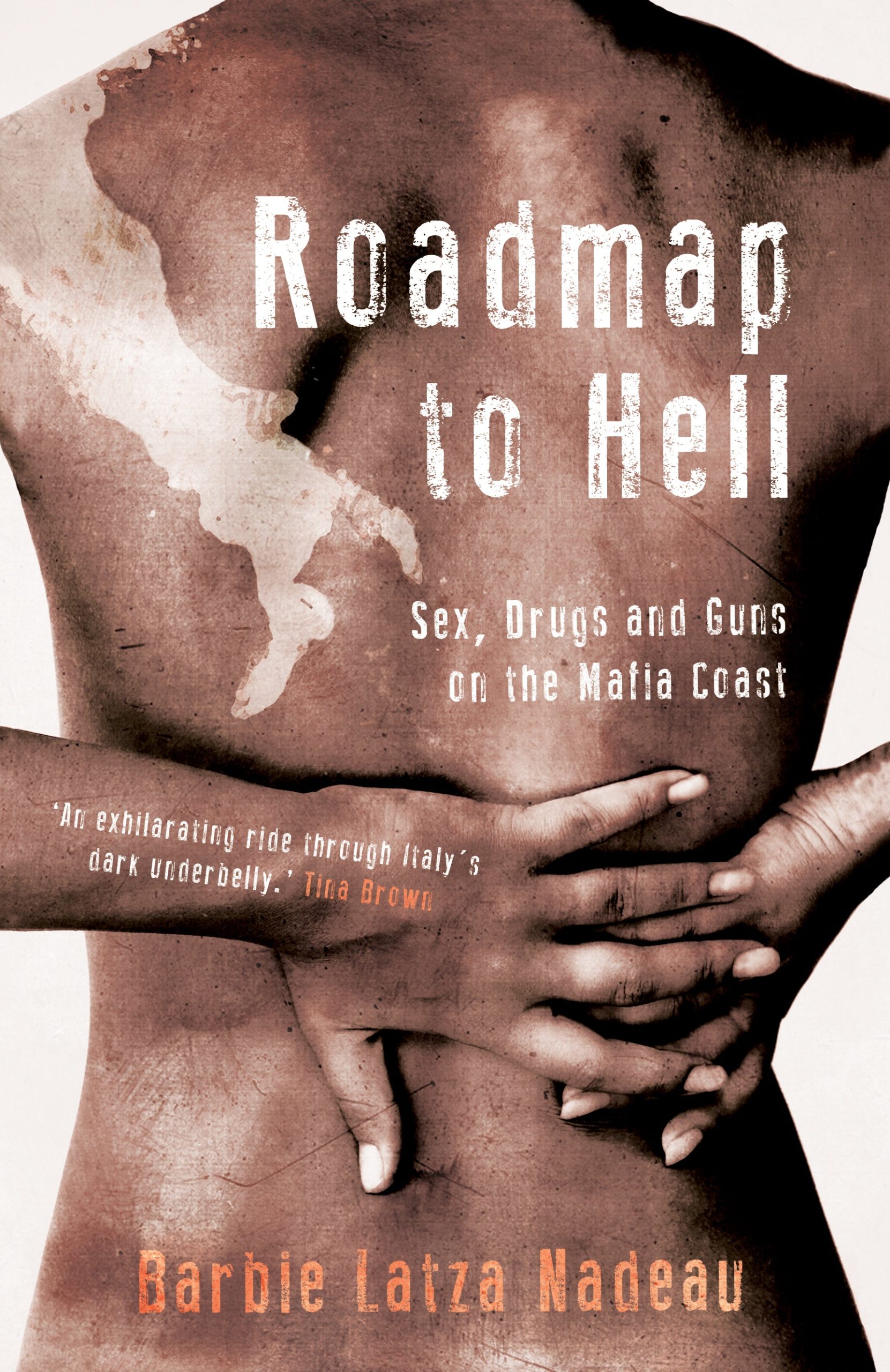

The scars on Rose’s body are like a roadmap of the hell she has endured. Cigarette burns from one client, a bent and broken pinkie finger from another. A thick, raised white line that cuts diagonally across her dark forehead down through her left eyebrow — a scar from a bottle that her madam broke over her head. Rose’s story of being trafficked from Nigeria to Italy as a sex slave seemed especially brutal. But when I asked Sister Rita, the nun who runs the shelter where I first met Rose, why she was so unlucky and why she had so many more scars than the other women, the nun corrected me. The only difference between Rose and the others, she said, was that the other women don’t talk about or show their scars.

I met Rose at Casa Ruth, a shelter for trafficked women run by Catholic nuns tucked along the main street in the Neapolitan Camorra stronghold of Caserta in southern Italy. It is one of the only places of refuge for sex-trafficked women who are forced to work in one of Europe’s busiest sex markets — the Via Domiziana, which intersects the nearby coastal town of Castel Volturno just north of Naples. In 2016, more than 11,000 Nigerian women came to Italy on the well-worn migrant trail which extends across the Sahara desert to the squalid detention camps in Libya before they even get to the Mediterranean Sea. The 2017 number will be slightly less, only because so many people are stuck in Libyan detention centers now. The International Organization for Migration says more than 80 percent of Nigerian women are trafficked for sex before they arrive in Italy. Many more fall into the trap once they reach relative safety. Most are between 14 and 20 years old.

Rose knew that she might end up in sex work when she came to Italy back in 2011. She had heard rumors of the sort in Nigeria, but had hoped it wouldn’t happen to her. In any case, she didn’t think she was attractive enough with her short, robust physique. Rose was told she could easily find work as a hair braider — a common lie used to lure women to Europe despite the fact that there are few salons that cater to African women in Italy. Those who fall victim to this lurid racket are told instead that there are many salons for all the successful Nigerian women who have come before them.

Like many Nigerian women and girls who end up in this part of Italy, Rose took part in a black magic JuJu ritual before she left her home in Benin City, but she doesn’t like to talk about it in detail because she still believes the curse could bring her harm. Most of the women who succumb to the ritual describe scenes that include the slaughter of goats or chickens. Most are also forced to leave with the witch doctor a little flap of skin cut from above their left nipple along with pubic hair and menstrual blood. The witch doctor wraps the items in a little package which is then used as leverage for the suspicious women who are told that as long as the witch doctor has their body bits, he has control over them. The ritual is usually performed in Nigeria, but there are also witch doctors in Italy who work with the madams.

Rose thought the JuJu ritual was just a promise to pay back those who helped arrange her journey. Her parents cobbled together what money they had to send with her. They viewed it as an investment so that she could soon start sending money home to help them. Rose estimates that she paid around $1,000, although she can’t be sure because at the time she didn’t know simple math or the value of money. But when she arrived, she owed her madam $56,000 to be paid back in sex acts for which she could charge no more than $25 a piece.

She says that she had too many bad experiences not to believe in the curse. “The curse cannot be broken,” she whispers. “Not even prayer can get rid of the JuJu.”

She doesn’t like the nuns who run the shelter hearing her talk about the fear she still has of the JuJu curse; and she will not share a single detail of her particular ritual, or the witch doctor who performed it. “Talking about it will wake the JuJu, so don’t ask me any more,” she pleads. Rose likes to hold the hands of people she is talking to and hers are always ice cold and clammy, which she invariably apologizes for. She says it’s because of the curse, that the spirit has deadened some of her soul.

***

Within a month of arriving in Italy, Rose found herself in Castel Volturno, north of Naples, working two different patches of sidewalk, one in the morning and the other in the afternoon. She stayed on the streets for three long years. Men often refused to pay her, telling her that she wasn’t attractive enough to charge for sex. She was frequently beaten by her madam when she didn’t bring in enough money. Her eyes swell with tears when she recounts how the clients often forced her to do degrading acts, beating her when she refused.

The sex acts forced upon Nigerian women are made all the more degrading because they often involve men who do not wash before picking up the girls. I have been told by many women that they carry around wet wipes and ask the men to clean themselves before they will perform oral sex, but many refuse because there is a sick pleasure in forcing a woman to put her mouth on an unclean penis. Hand jobs are also common, with women being forced to let the men to ejaculate in their mouths. Full intercourse is less common, in part because it is more expensive for the men and entails going to a madam’s connection house or finding an area outside. Clients often do not wish to have sex in their cars out of fear they will make a mess that their wives or girlfriends might find. Women told me stories of intercourse turning into anal rape, or how men insert objects like tree branches or metal pipes into their anuses or vaginas.

Many of the clients who pay for intercourse do ask for anal sex, which is something not all girls concede to, and certainly something they charge more for if they do. Some of the sex slaves who are forced to turn up to twenty tricks a day or more admit to applying a deadening cream to their vagina or anus so they don’t feel anything at all. More than one woman has mentioned an injection like Botox that can be self-administered to essentially make repetitive sex less painful.

Rose lived in a rundown connection house off the Domitiana Way, where she would bring men from the street. The house was in the complex of single-story villas built for the Coppola Village estate, but the houses had been abandoned when the whole area was confiscated by the state because it was illegally built at the hands of the Camorra, so there were no appliances and the plumbing was very basic, with a toilet that had no seat on it and just one sink that the girls who lived there used for cooking and bathing. A thin tube was attached to the sink since there was no shower stall or bathtub. The villa had no heating and in the winter months they had to use a propane heater that sometimes sparked and caught the curtains on fire. Rose said sometimes she worked twenty-four hours a day, often turning a dozen or more tricks without sleeping. Her goal was to pay off her madam, but she somehow never got ahead.

Rose wasn’t formally educated in Nigeria and although she could recognize letters and read some simple words, she was not skilled at all in math when she arrived. She had no choice but to trust that her madam was accurately deducting her earnings from her debt. But whenever she asked, it seemed she had been charged for more clothes or rent or food and she never caught up. She had no basis from which to argue, however, because she didn’t really understand the numbers.

Eventually, Rose fell in love with a young Nigerian man whom she met at an underground party in Castel Volturno Destra, held at a former pizzeria where Africans would gather to share traditional music and food. Rose’s boyfriend was also bound by the JuJu curse. The ritual used on men is slightly different from the one women take part in and often includes flagellation and other forms of self-torture. He was from Borno State in the north of Nigeria and had left to avoid being recruited by Boko Haram militants who had convinced many of his friends to join their cause in its infancy, long before they gained notoriety by abducting the Chibok girls in 2014. He was denied asylum in 2012 and given ten days to leave Italy, but the authorities didn’t give him any financial support or a plane ticket to do so. Instead, he was recruited by the Neapolitan Camorra to run drugs.

Rose and her boyfriend left the Via Domitiana together after she became pregnant with their daughter. But not before Rose was beaten senselessly by her madam, who was angry with her for not being more careful. Rose forced her clients to use condoms by lying about being H.I.V. positive. In order to separate the act of paid sex from the intimacy she shared with her boyfriend, she didn’t use a condom with him, she says, even though she knew the risk of pregnancy was high. Her madam told her to keep working during the pregnancy, saying she could take some time off after the delivery. She would arrange for a babysitter, but, of course, Rose would have to pay extra for that.

Once Rose and her boyfriend escaped the Domitiana, however, her battle was far from over. Her boyfriend took a job as a bricklayer at a construction company run by the Camorra near Caserta and Rose stayed at Casa Ruth until their baby, Faith (a common name for babies born under Sister Rita’s watch), was born, in part to try to improve her reading and learn simple math. Eventually, Rose found a job with a company that provided cleaning services for an American military base near Caserta. The nuns and other women took care of Faith at Casa Ruth while she worked.

But the people running the company that cleaned for the Americans were corrupt — and mean. Rose was beaten, verbally abused and paid slave wages for excruciating work under often-dangerous, toxic conditions. She finally left the cleaning company, but not before her manager threatened to kill her and her baby. Rose left anyway. As she tells it, this is the work of the JuJu inside her soul for betraying her madam.

Shortly after leaving the cleaning company, Sister Rita convinced Rose to start working at the New Hope Cooperative, a sewing shop run by Casa Ruth to help sustain the women rescued from the streets. She and her boyfriend eventually moved into a small one-room apartment in the center of Caserta and they plan to get married one day. Sister Rita has pushed Rose to challenge herself, telling her that she will only succeed if she takes safe risks. To do that, Sister Rita is training her to run the cash register at the boutique. Several months after I first met Rose, I returned to New Hope and bought a hand-sewn notebook cover made from dark-green fabric that came with a green pen with the New Hope logo. Rose counted my money and gave me the change and carefully wrote out a receipt as Sister Rita looked on with the pride of a mother whose child had just graduated from Harvard.

Still, Rose worries about the JuJu curse. She has become a devout Christian and she has tried to replace that fear of the spirits she believes still possess her with faith. But even that is difficult. Her eyes well with tears again as she explains that she hopes all the gods will forgive her for what she has done — the JuJu “god” for breaking the curse, and her Christian god for what she says are her sins of selling her body on the street.

But the worst part of Rose’s story is that she still plans to pay her madam back one day, even though she is free from the slavery that kept her on the street. It is common for women who escape the streets still feel the weight of the financial burden, often convinced they still owe the hefty debts or something terrible will happen to them because of the JuJu. “That’s the only way to really break the curse,” Rose says. “How can I not pay the debt?

*From* (1). *Used with permission of Oneworld Publications. Copyright © 2018 by Barbie Latza Nadeau.*

1) (https://www.amazon.com/Roadmap-Hell-Drugs-Mafia-Coast/dp/1786072556)