Nona called me from Chicago and said, “Emma’s dead,” and I started laughing because I didn’t understand what she was saying. I repeated it to my boyfriend, whom I’ll call Reis here. He was sitting right next to me, and I watched his nose crinkle and his head cock, and I was rewired so fast. I began repeating “Emma’s dead” over and over again, at top speed, out loud. Eleven days later, Reis sat in front of me in my childhood bedroom on the Upper West Side of Manhattan while I practiced Emma’s and my favorite camp song, “Changes” by Phil Ochs, all morning before I went to sing it at her funeral. It was at a stodgy funeral home meant for the very old, not the very young like Emma. And the funeral was a lot like the funeral home. It was very cold; lots and lots of poems were read, but I couldn’t feel or see Emma anywhere. An impossibility, I suppose, since she wasn’t there.

But Emma would come alive in my dreams. So I slept. I slept, and slept, and slept. Once, I dreamed we were back in our Quaker high school, Friends Seminary, sitting with the seniors, looking out onto the rest of the school during silent meeting, laughing hysterically. It was so close to real life: in high school, we’d often muffle our laughter with scarves when it was cold, or each other’s bare shoulders in warmer months. But my eyes were forced open (by her ghost, I was sure) when I had dreams that were always too close to real life. I’d cry, shaking and confused at what the real truth was. The line between life and death, between this world and neverness, had never been so approximate, so shriveled. Reis held me every time I woke up until I was sure Emma was gone from the room. Until I was able to recall her death.

I stopped wanting to see alive Emma, so I stopped sleeping. Dead Emma, I didn’t want her either, and my relationship with Reis, unfortunately, was a casualty in all that. We didn’t break up, but I couldn’t look at him without seeing Emma. We became distant. Housemates who sometimes had sex and occasionally made granola together.

***

> The line between life and death, between this world and neverness, had never been so approximate, so shriveled.

I was skinny and sleepless from dead Emma when I saw a friend who I’ll call Wade. He was with some other boys I grew up with on a balmy night in March at Botanica, our old underage haunt. My hair was frizzy, and I was insecure about that. Wade’s already-olive skin was extra browned by a birthright trip to Israel and his rogue travels through Jordan. His blithe enthusiasm for the dog tags that hung from his neck, given to him by a young Israeli soldier, was trite. But I didn’t mind. His energy hooked me. He whispered in my ear all night, looked at me goofy on purpose, and asked me to the movies. The next evening, Wade and I went to a movie because Rosario Dawson was in it and we both thought she was a total babe. Afterward, he walked me to Sadye and Jesse’s, where I had to sit shivah because Jesse’s grandpa had died. We walked two miles from the theater to their house, never missing a beat. Our banter was so entertaining, I wanted to remember every word and turn it into a scene in a romantic comedy. Right before I went upstairs, he tried to kiss me. I told him that I couldn’t, that I had a boyfriend. But dead Emma, I couldn’t yet tell him about.

I saw Wade at least three times a week after that. We spent a lot of lazy afternoons on the Upper West Side, sitting in Riverside Park, laughing really hard about how often the two of us, more than anyone else in the world, had to pee. We made plans to travel, but not to obvious tourist destinations. We would go to Russia, the most foreign place we could think of. When I said I’d heard it was racist, he told me he’d do his best to protect me, at least until a mobster came and took me away. In May, for my birthday, he got me a guidebook to the country. On the first page he wrote “For us, Russia 2010.”

We went to concerts and made each other mixes sent over Dropbox. He called one mix “Russia 2010,” and the first song was “Stop the World,” by the early-2000s crooner Maxwell. I remember listening to the lyrics “‘Cause when I’m here with you, the world stops for me” like it was Wade’s ode to me. We reminisced about growing up in the same neighborhood and how we’d always been friendly, but never close. I made fun of him for working out obsessively in high school, for dressing and acting not like a Jewish kid from the Upper West Side but an Italian-American kid from Long Island. Whenever we’d walk, I’d latch onto his arm; it felt like kissing. Once, while his friends were watching the Super Bowl, he pulled me into a room and we nearly did. The moment felt more erotic than tons of sex I’d actually had.

One day in late spring, we walked by Emma’s house. I’d been very cautious to avoid her building and all the stuff of her, but I’d forgotten to be vigilant with Wade. Because Emma wasn’t dead with Wade, she just wasn’t alive.

I waved at Emma’s doorman, mechanically at first. He was tall as he’d ever been, and I was reminded of his infectious smile, but didn’t look. I hurried by, but when I looked back I saw his watering eyes, and I became very dizzy.

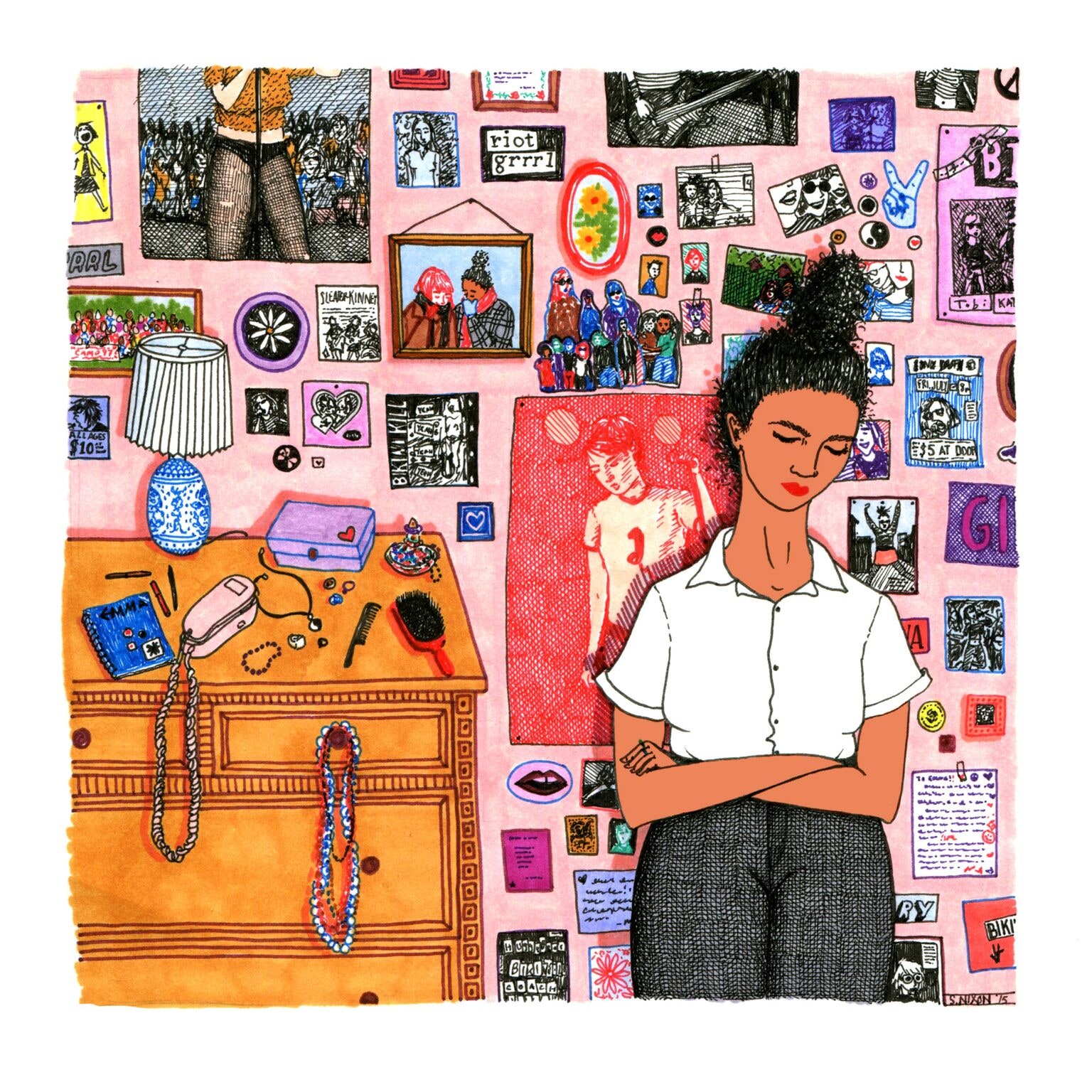

“Emma died. My friend Emma. Do you remember her? No? She was into Kathleen Hanna and dyed her hair lots of colors. She was my best friend. You didn’t know her well I guess. But surely you must remember her. You went to the same elementary school, P.S. 87.”

I watched Wade feign recognition. For my sake, for his. For the sake of keeping together our unmistakable dream world where we understood each other’s every note, look, and touch. Quickly, we became lost in the loop of a corrupted fantasy; our buoyant relationship turned heavy and fraught. Quickly, I realized part of why I loved Wade was because he let me forget Emma. And because with him, and only him, I felt drunk on a sanity I never thought I’d regain. With him, I was Collier before “Emma’s dead.” On many occasions after that day, I told him about Emma. We spent hours on street corners late at night screaming about what we were, about what we weren’t, and why. The insanity I felt about losing Emma, it was clear, I was transferring to the possibility of losing Wade. I screamed about how bad I felt about the girls he fucked, scenester white girls who wore neon sports bras to the club, girls who matched the new DJ persona he was trying to hone. Fighting felt good. I came to realize how hollow I’d felt before.

> We spent hours on street corners late at night screaming about what we were, about what we weren’t, and why.

And we’d find our way out, somehow. Once, during a particularly bad clash, a rat ran across our path, and in a split second we grabbed hands and raced down the Lower East Side street, dawn’s light creeping up, laughing so hard my insides felt pummeled. Another time on Chrystie Street, after his bartending shift, he told me I wasn’t his type. Seconds later, we heard two roosters, their crows entirely fractured. For the rest of the night, I forgot what he said.

***

Time is the only thing that really assuages grief, and real time began to pass. I missed alive Emma less and accepted her death more. But the memories and fantasies about the time I spent with Wade in those first few months crystallized into fairy tale, a time when nothing was wrong, a time before pain.

I let two years go by like this. Back and forth with Wade in a friendship that needed a different title. I spent that time clinging to every word he’d said to me about how important I was to him, how he revered me, saw me in a way he saw no other woman. He got a girlfriend right around the first time I broke up with Reis (we’d break up three more times after that).

Wade’s mounting indifference drove me mad. I convinced myself that if I’d never told him on the street corner that day about Emma, everything would have turned out differently. _Her death ruined my life,_ I thought. Me and Wade went through long spells without speaking to or seeing each other. And when we did, it was always stilted; he was so foreign. My heart always beat too fast, and my mind raced for the right thing to say to get him back to wanting me again.

> He looked at me, knew this was the crescendo in our film, and said softly, so I could barely hear, “I’m sorry, I can’t.”

I made one last attempt.

After Reis and I finally broke up for the last time, I tried in earnest to be with Wade, to break our pattern, to make it so that he’d hurt me so bad the spell would finally be broken. A week after he’d ditched me at Sadye’s wedding for a party in Manhattan, I asked him to meet me. Sweating through my denim dress on the steps of the New York Public Library, I told him that I wanted to really give it a try, that I wanted him to learn me deeply and wholly. He looked at me, knew this was the crescendo in our film, and said softly, so I could barely hear, “I’m sorry, I can’t.”

We don’t talk, me and Wade — not often anyway. At our friend’s wedding last year, he played out a scenario of our future wedding, in a Vermont blueberry field. A throwback to old times, I think.

I loved Wade to unlove Emma. But I’ll never unlove Emma. I thought I’d never get to be as happy as I was when Emma was living. Wade was a divine providence who showed me happiness after tragedy can exist, even if I have to shape it, will it.

I miss Wade all the time, every day. How impossible life would be without the option to retreat into fantasy.

_Collier Meyerson is a reporter at Fusion and lives in Brooklyn._