My plane from Oslo arrived in the town of Longyearbyen after midnight. I was seated next to a weathered Frenchman and an American girl who chewed her gum with oblivious passion — all of us were awake and celebratory after the three-hour flight.

I had come to this Arctic island, Spitsbergen, part of the Svalbard archipelago, mostly on impulse. After I decided to go, I planned to note the effects of the extreme cold and majestic whiteness while living as an artist-in-residence at the world’s northernmost art gallery, Galleri Svalbard.

When I stepped off the plane to wait for Andreas, the guide who would drive me into town, the cold hit me hard. I staggered backward, sputtered, and coughed. During my five-day stay there, the temperature never rose above 5 degrees Fahrenheit (the low was negative 20). The cold was so severe, it could best be described as lethal.

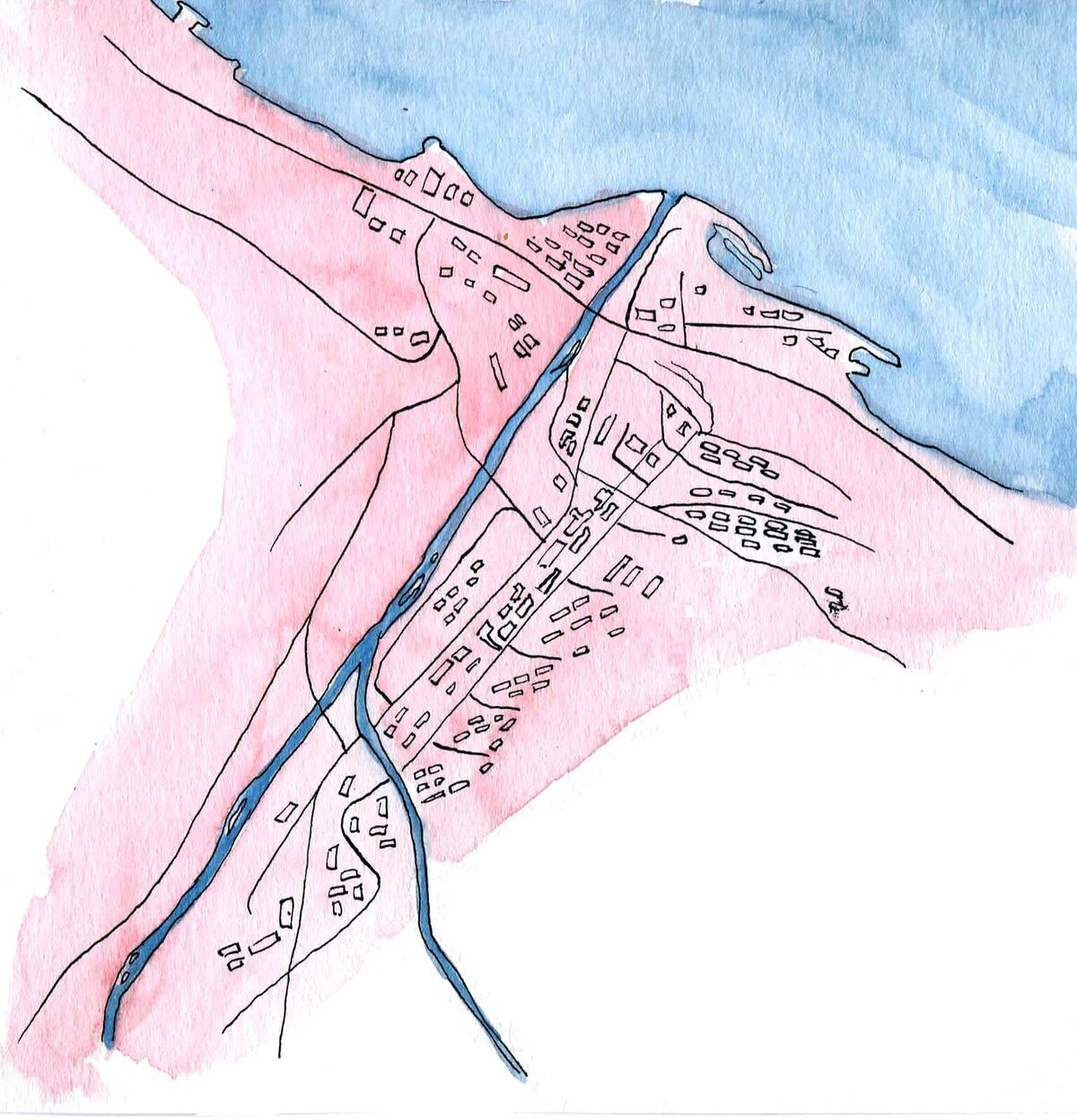

The Svalbard archipelago is located at 78 degrees north, 12 degrees from the North Pole. Shaped like a uterus and home to the world’s northernmost civilian population, the archipelago, which have belonged to Norway since 1920, are cold, kind, and human. The local inhabitants are outnumbered by polar bears, and for everyone’s safety, people are required to carry flare guns and rifles or travel with an armed guide if they go outside the populated areas, represented in pink on the map.

***

My first morning, Andreas picked me up for a snowmobile safari. I learned that while he was originally from Thüringen, Germany, he was one of the first tour guides on Svalbard; there was no one more knowledgeable about the islands.

We drove up the mountain behind Longyearbyen; from this vantage point, the town and the fjord plunged into the Arctic Ocean. The land was vast and pristinely white — alien and surreal. The wind twisted the snow into ghostly wisps, but underfoot, it was so compact it could make a snowmobile buckle. I saw a Svalbard reindeer, the archipelago’s eponymous subspecies, for the first time. They are an odd, hunching product of this extreme environment: small, with dirty white coats and comically short legs, they’re surprisingly able to outrun polar bears.

Now on foot, Andreas and I hiked farther up the mountain. We came across the crash site of Vnukovo Airlines Flight 2801, where there’s still scattered debris and a mutilated plane wing, along with a makeshift memorial. The 1996 crash killed all 141 passengers onboard; most were relatives of Russian coal miners. Pyramiden, the site of their mining operation, was abandoned two years later.

On our way back, we drove around the bay facing Longyearbyen, stopping to walk along the black pebbled beach. I pocketed a few stones like a visitor to the moon. There is an abandoned mining town up the hill that dates from the 1910s. Stilted homes stand in disrepair, and a rusty Ford pickup is half-buried in the snow. The gears and cogs of a dilapidated power station face the glazed fjord, and the sky has faded into a thin strip of pink horizon. The view here is desolate.

The next day, Andreas took me along Longyearbyen’s coastal road, which runs parallel to the shore for ten kilometers on either side. Toward the airport and wedged into a mountainside, facing the ocean, we saw the Svalbard Global Seed Vault, which stores seeds from countries around the world. Foolishly, I asked whether it was heated and if I could go inside. The answer to both was no.

***

For my third day in Svalbard, I had signed up for an ice-caving expedition in a glacier. I was attracted to the mix of comfort and adventure in the event description: “Pickup to and from accommodation, cookies and tea.” By 9:01 a.m., I was ready and waiting. A handsome and mysterious man finally arrived, twenty minutes late, in full expeditiongear. He sized me up and announced that we were headed for a three-hour hike up a very steep mountain slope and I would not withstand it. Emboldened by the challenge, I declared that I was more than capable, and even more equipped, and that we should really be going already, shouldn’t we?

Within five minutes, I realized that I was neither equipped nor capable. My boldness was no match for the physical reality of the mountain peak ahead. I whispered breathless and desperate prayers as I watched while my team went on without me. Only one participant, Alastair, stayed with me. He cheered me on, but alas, I looked at the oblivion around me and sobbed. We went back down into the valley and saw the glacier from there, its blue and beautiful protrusions. We sat in the snow for our tea and cookies.

***

A bus picked me up at dawn on my fourth day in Svalbard. I was going to Pyramiden, the Soviet coal-mining town that had been abandoned two decades earlier. The view from the boat that would take us there was stunning: The water was black, the sky was gray, and the ice-covered mountains surrounding the fjord sparkled. Farther along the trip, the fjord grew icy; inch-thick layers broke against the boat’s hull in wide sheets, like the punctured crust of a crème brûlée.

As the ice got thicker, the boat couldn’t go any farther. We were just ten minutes from Pyramiden’s harbor, so we disembarked and walked to shore. I had heard that earlier in the week, a man had fallen through the ice and had then been fished out and left behind to thaw; it was somewhere near here, and I was careful.

Once at Pyramiden, our guide greeted us with jokes he’d surely told hundreds of times. He added, in his thick Russian accent, “Stay close. Last year someone wandered off and was eaten by a polar bear.” We didn’t know whether to believe him; either way, after walking for only a few minutes, our group carelessly dispersed.

We learned that Pyramiden was conceived by the Soviets as an Arctic Utopia, with its mines of purest coal. But the idealism of the town’s origin is glaring in contrast to its present, dilapidated state.

First, the guide took us to the cultural center, which sprawled behind the “earth’s northernmost bust of Vladimir Lenin.” Apart from visitors like ourselves, the building was abandoned. On the second floor, there was a particularly interesting room used for storing and projecting film, one of the amenities that made Pyramiden more hospitable to coal miners in the 1970s. The room had fallen into a state of disarray, and there were still remnants of the past. The floor was carpeted in celluloid and technicolor ribbon. I picked up one strip, and I swear I recognized Rex Harrison and Elizabeth Taylor in _Cleopatra._

We finished our trip in town at the Hotel Tulpar bar. It is in the only building on the settlement with heating and water, home to six residents and a few occasional guests. The bartender was boyish and fresh. His eagerness to please was youthful and heartbreaking. I could not buy a drink because they don’t take credit cards that far north, so I returned to Longyearbyen, where I met up with Alastair. We drank white Russians and stayed up until the arctic sun shone brightly.

Later that morning, foggy-brained and irritable, I got on a plane back to Oslo. It flew below the clouds, over spectacular vistas. The captain’s voice described the peaks, glaciers, and fjords below, and I was lulled into a dreamless slumber.

_Naï Zakharia is an illustrator, editorial designer, and part-time contrarian. You can find more of her illustrations at_ (1) _and follow her on Instagram at @naizakharia._

1) (http://www.naizakharia.com/)