So. I was a loser. I found this out when I wore a furry, bright-red cowl-neck sweater to school one day, and Lisa said, “Where did you get this thing? Bi-Way?”

Bi-Way was a chain of Canadian stores that sold cheapo merchandise: badly stitched muumuus; “three T-shirts for the price of one!”; candy dispensers that were also mini fans that stopped working after one use; fake Barbies with giant heads and breakable plastic limbs. I’d gotten the sweater at Zellers, which was also a chain of stores, but a few grades above Bi-Way. I told Lisa proudly where the sweater came from and she said with a smirk, “Nice socks.” They were, indeed, nice — as fiery red as the sweater: I liked to match.

“Say _vagina,_” Lisa said before walking away with her posse of cool girls, and I said vagina, and they laughed. Later, I looked up vagina in my dictionary.

Fuck.

That was in grade nine, and I had been in Canada for about three months by then. I knew almost zero English, except for the names of vegetables that my elderly English-as-a-second-language instructor was adamant about teaching us in the summer, when we first arrived from Poland. He would frequently take us to the grocery store and introduce cucumbers, carrots, and apples to our new vocabulary.

> That was in grade nine, and I had been in Canada for about three months by then.

The problem with the sweater, as I found out later, was that it was not a “label” — not Calvin Klein or Tommy Hilfiger — plus, it was the kind of sweater a girl my age, back then, would never wear. The cool girls, skater girls or girlfriends of skaters, wore oversize T-shirts, loose pants, and Vans or Airwalks. The other cool girls wore skirts and tight shirts and they smoked cigarettes in the parking lot and giggled with boys who wanted to get with them.

There were some Polish kids in my school, but they all knew one another from elementary school and they were a tight clique. The city I’d moved to was small (36,000 people), and most of the other Poles had come from even smaller villages. Sometimes entire villages would immigrate: uncles, cousins, and grandparents would pick up their lives and move en masse. A sponsor — an established Canadian citizen of Polish heritage who could vouch for one particular family — would bring a family, and then once that family established itself, they would sponsor another one, and eventually the village would start emptying out. Everyone would catch the virus of immigration. The reason? People in North America had VCRs and Mars Bars that in communist Poland were available only in concession stores like Pewex (now the name of an ironic hipster bar in Warsaw) and only if you had American dollars. So by the time we got there, my Canadian city already had a bunch of “_ski_s” in it — the last three letters of almost every Polish name being basically the same, including mine.

The children of those immigrants were known in my school as the “Polish mafia,” and they were an impenetrable group. My main disadvantage was that I came from a big city — Warsaw, the capital of Poland. I was immediately dubbed a “snob.” I didn’t help myself by behaving like one and complaining about the crappy town we lived in. (Consider this: the most exciting venue was the dumpster behind 7-Eleven, where you could drink fluorescent slushies and smoke pot if you were cool and had pot.)

As fall turned into winter, I wasn’t progressing: I was still trying to match my tops with my socks. And I couldn’t afford to spend the money I made at Wendy’s — my first job, hands smelling of mustard and ketchup for days — on labels. I was saving up for a ticket to Poland, to run away back to Warsaw after the school year was over.

> As fall turned into winter, I wasn’t progressing: I was still trying to match my tops with my socks.

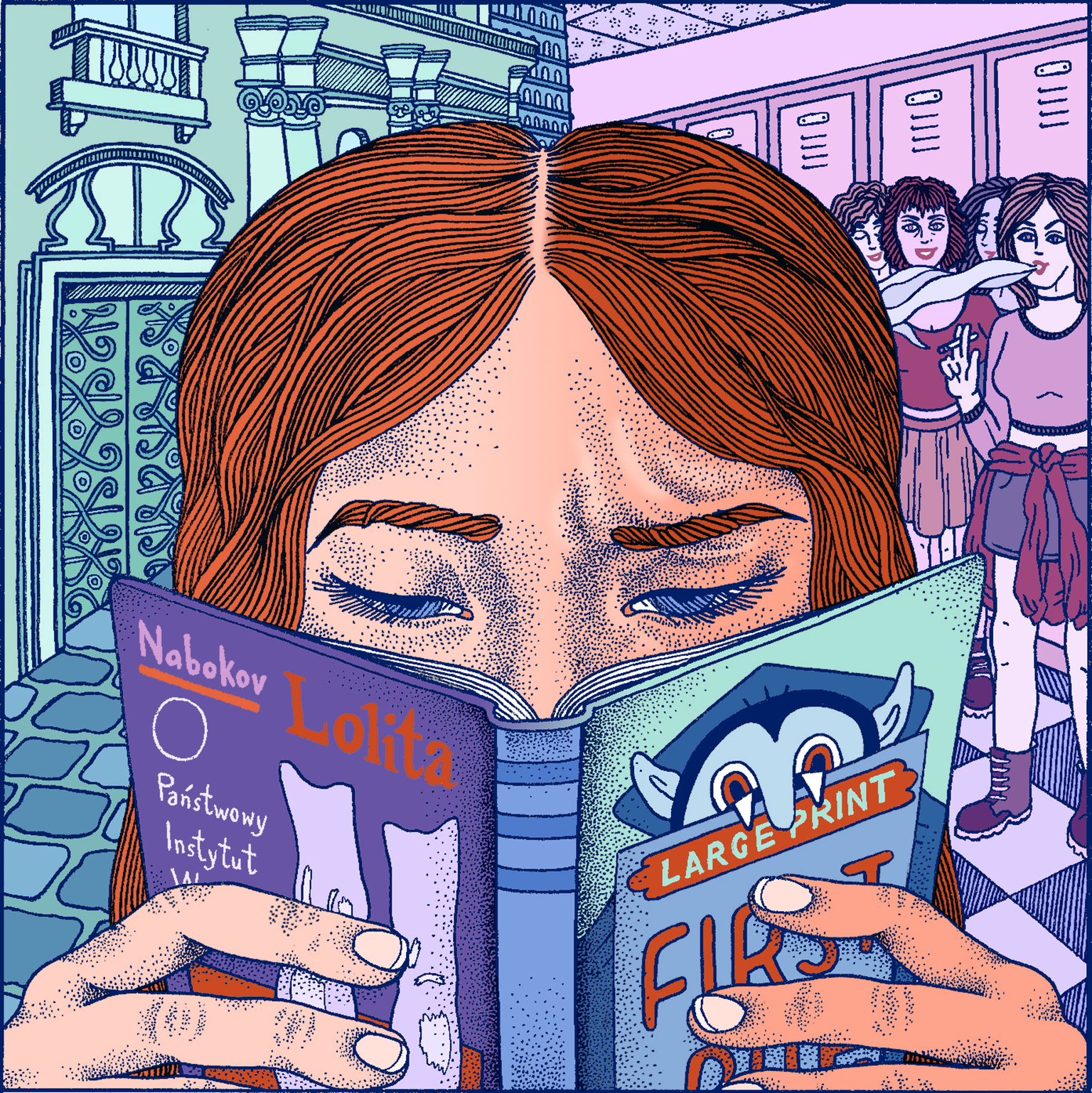

At school, I spent my lunches at the library — my safe place, a library, always. I was mesmerized by the glossy magazines: _Sassy_ and _Seventeen._ I learned how to dress from them — no more matchy matchy. I found out that flowered grunge dresses were in, and I bought my first pair of Doc Martens and an oversize sweater that had the right designer label from a secondhand store. I was finally getting the look. I still had no friends, but my dresses were like camouflage — I could hide better; the teasing stopped.

I remember wanting to befriend Nancy, who seemed really sweet. I practiced for hours how to ask her in English to borrow an eraser, but when I tried she couldn’t understand what I was saying. The only person who accepted me was Sarah, who was developmentally challenged. Part of me felt even more desperate about my loser status when I sensed her trotting behind me. At the same time, her existence made me feel better because she proved there were people below me in the high-school hierarchy. I ignored her, and eventually she got the hint. Sarah is one of the few people I still think about when reminiscing about St. Mary’s. I feel guilty about how I treated her, but I would never contact her to apologize. That life is gone forever, and with it, Sarah.

My English was improving slowly because of my frequent visits to the library. I would borrow books with large fonts — young-adult books usually, with some supernatural bent where a girl was secretly a vampire and a boy was a werewolf. In Polish I read canonical literary novels — _Lolita_ and _1984_ — but in English I had to be a twelve-year-old for the time being.

> My English was improving slowly because of my frequent visits to the library.

I also rented out old movies like _Cleopatra_ and _Gone With the Wind_ and watched them in the slow, boredom-filled afternoons. The popular girls in Airwalks skateboarded on the streets with boys who loved them.

Despite my movie-watching and reading, I still had a lot of problems understanding the new language. Before exams, I would study definitions and formulas without really absorbing the words behind them. I would memorize them the way one memorizes poems: “Velocity can be positive or negative. A positive velocity points in the direction you chose as positive in your coordinate system. A negative velocity points in the direction opposite to the positive direction.”

Whatever that meant.

Once, trying to be clever, I wrote on a page of my exam, “On the next shit,” meaning “sheet.” The science teacher gave me an F. There were other, similar, screwups. When a boy I liked who flipped burgers with me at Wendy’s asked me to “see a show,” I didn’t understand what he was asking me. Just in case, I said “no” quite enthusiastically. Years later, I remembered the exact words and felt sad for both of us.

Eventually, as time went on, my English improved enough that I was able to communicate with people, and I made a new friend — another Polish girl who was also an outcast due to her mean nature. She loved to offend people; her primary language was neither Polish nor English, but Sarcastic. I became her minion and trailed behind her to parties where we would drop acid or smoke pot and drink beer. I hated pot and acid, but beer made me more confident and miraculously made me speak English much better — or so I thought. Either way, with my new skills and false confidence I was able to talk to boys and started going on dates. My first serious boyfriend was a skater who was also a small-time drug dealer and further helped me to shed my loser status.

I changed schools, too, from my Catholic school to a public one, where I reinvented myself as “goth.” I hung out in parking lots and smoked cigarettes and rolled my eyes when I couldn’t recall how to say things. That was acceptable, and in my senior yearbook I had lots of signatures, some with declarations that I was a “cool cat” and that it was great to know me.

> I changed schools, too, from my Catholic school to a public one, where I reinvented myself as “goth.”

By the end of high school, my reading and understanding of English was fluent enough that I managed to get into my top-choice university to study psychology. I survived the next four years on B’s and C’s with an occasional A. In my third year, while studying for a statistics exam, I wrote a short story about a man who gets killed by a vending machine and submitted it to a fiction contest at our university newspaper. It was accepted, and people talked about it. I barely passed the statistics exam, but I now had an idea about what it was that I was really good at: language.

As I progressed in my career as a writer, I realized that language is not something that’s for pleasing other people, or about fitting in. It’s about expressing something much more elemental. People have asked me what language I think in. But that’s like trying to define what home is, what dreams are, how you dream. After I emigrated from Poland, I had one recurring image in my head. Cobblestones. What I see is my feet walking on cobblestones on the way to the church where I had my first communion. I don’t care about the communion anymore, but the cobblestones vision still hurts, still makes my chest seize. Whenever I meet someone who has immigrated to Canada, I wonder about his or her country. What are they missing? Cobblestones? A white-sand beach? Favelas? Gargoyle sculptures? Music? Unpaved roads? The entire city of Lisbon?

I have two homes.

I write in one.

The other one is my soul.

_Jowita Bydlowska is the author of a memoir,_ (1)_, and a novel,_ (2).

1) (http://link.lennyletter.com/click/7424950.12/aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuYW1hem9uLmNvbS9ncC9wcm9kdWN0LzAxNDMxMjY1MDQvcmVmPWFzX2xpX3RsP2llPVVURjgmdGFnPWxlbm55bGV0dGVyLTIwJmNhbXA9MTc4OSZjcmVhdGl2ZT05MzI1JmxpbmtDb2RlPWFzMiZjcmVhdGl2ZUFTSU49MDE0MzEyNjUwNCZsaW5rSWQ9ODc0OTVkMzg0YzgxNzVkZGFlODM3NzEwN2IxM2RjYjI/5672eded1aa312a87f2d6890B5a4f346a)

2) (http://link.lennyletter.com/click/7424950.12/aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuYW1hem9uLmNvbS9ncC9wcm9kdWN0LzE5MjgwODgyMzYvcmVmPWFzX2xpX3RsP2llPVVURjgmdGFnPWxlbm55bGV0dGVyLTIwJmNhbXA9MTc4OSZjcmVhdGl2ZT05MzI1JmxpbmtDb2RlPWFzMiZjcmVhdGl2ZUFTSU49MTkyODA4ODIzNiZsaW5rSWQ9MTJkYTliOGJjOWVhMDA4OTg5MzkyNjY1Y2RlZTdjNWI/5672eded1aa312a87f2d6890B556e672d)