Growing up, I was always more comfortable with adults than kids my own age. I was an only child, my single mother worked long hours, and I spent a lot of time hanging out with much older people. My best friends were my babysitter Mrs. Stobie and my neighbor Mr. McShane, both of whom were in their 60s. We played Rack-O (great game, by the way) and listened to NPR. They encouraged my love of Shakespeare and George Bernard Shaw; my interest in the past was cute and precocious to them but bizarre to my peers. Two girls dropped me as their best friend in elementary school because I was dead weight — you’d never become popular with me hanging around. But what my classmates thought of me was less important. Pleasing adults made me feel safe and secure; my parents divorced when I was two, and I sometimes felt more like a mediator than their child. When it was calm with them, it was calm for me.

This translated beautifully into my passion for theater. Directors and stage managers loved my desire to be obedient and cooperative. Showing up on time, learning your lines, being quiet backstage, and remembering basic stage blocking get you a lot of praise. I developed close mentor relationships with acting teachers and directors, and the theater was my safe zone. People were nice to me there, and acting came naturally.

When I was accepted at The Juilliard School, it felt surreal. Thousands of people audition, and they accept around 20 actors per class. To quote Melanie C’s song “Rising Sun,” “I’m filled with hopes I never dared to dream before.” It felt like such an endorsement of me as an actor, maybe even me as a person. This meant I wasn’t deluded; I was good enough to be a professional actor. It was also a chance to move to New York City and individuate from my mother. The faculty will love me just like my acting teachers and directors did back home. I’ll play Rosalind in *As You Like It* and Beatrice in *Much Ado About Nothing* and perhaps even tackle Hermione in *The Winter’s Tale* — I’d already memorized her big monologue.

I couldn’t have been more wrong. It started going south on the very first day.

At Juilliard, attendance and punctuality are very, very important. If you’re late three times, it counts as an absence; if you’re absent five times, you’re placed on probation. Probation means you could be expelled at the end of the school year. This was no problem for me — I’m always on time and usually early.

The first class for freshman is an early-morning movement class. I showed up, on time (duh), and was immediately chastised by the teacher in front of the whole class for being tardy. This was horrifying. I had been so careful; how could this have happened? Thankfully, my classmates came to the rescue and pointed out that the classroom clock was fast. The teacher backpedaled into a lecture about the importance of punctuality, but the experience was unnerving.

It didn’t get better from there. It seemed I had an intellectual understanding of what the faculty wanted but was unable to “get out of my head,” as acting teachers are fond of saying. I also had bad posture and shuffled my feet: “You’re a pretty girl with such *UGLY* physical habits. I don’t know if we’ll ever be able to undo them.” My movement work was subpar: “You do well for someone with no natural ability.” But worst of all was my obedience. What had been my greatest strength was now perceived as laziness and passivity. It seems I had been trained too well as a kid actor. Instead of showing initiative and having opinions about my characters, I dutifully waited to be told what to do.

It all came to a head the week before Christmas break of my sophomore year. I saw my name on one of five yellow envelopes pinned to the bulletin board. The awful knot in my stomach told me what it meant: I was on probation. Probation was the elephant in the room at Juilliard. There weren’t any set quotas, and in theory they didn’t have to cut anyone, but every year I was at Juilliard at least one person was cut from the sophomore class. Two people had already been cut from my class because of absences and tardiness. But I was on probation because they thought I was a bad actor. Admittedly, I was lousy in the George Abbott play *Broadway*.

As soon as you’re placed on probation, you meet with the entire faculty as they tell you one by one how you’re failing in their individual classes. It’s humiliating, but I tried to keep a stiff upper lip. After the third or fourth teacher, I went into a kind of fugue state. I couldn’t even hear what was being said; I was just focused on not crying. Even then, my goal was to be a model student. I wanted them to be proud of how I handled the news.

That Christmas break was horrible. I decided not to tell my mother I was on probation. Throughout my childhood, my mother was very concerned that I would do *something* to jeopardize my future. This *something* was always vague, but probation at Juilliard seemed to fit the bill. She had already expressed concern that in going to Juilliard I was giving up a liberal-arts education. Juilliard offers almost no academic classes and is really more like a trade school than a university. (Albeit a trade school where you learn how to breathe and pretend to drink a glass of orange juice). I also felt my mother had a tendency to overreact to minor things. For instance, I cut school only once in high school, to — I swear this is true — go to a museum. My mother found out, turned me in to the school, and insisted that I apologize to all my teachers for disappointing them. In light of all that, I didn’t know how to tell her all my teachers at Juilliard thought I sucked. Looking back, I never gave my mother the opportunity to be supportive. Keeping it a secret made the burden that much worse, but in the moment, it felt like my only choice.

I started obsessively running through scenarios of what would happen if I were expelled. Would I still pursue acting? In my mind, Juilliard’s approval meant I had talent, and without it I should probably give up. The rational part of my brain knew this was stupid — many now-successful actors were expelled from Juilliard and did just fine. Would I reapply to an academic institution? That was going to be tricky, because none of my credits from Juilliard would transfer, and I’d essentially have to start all over again, as though the last two years had never happened. I felt my only option was to white-knuckle it through the second semester and try to become whatever the hell they wanted me to be.

I returned to school depressed and scared but intent on pretending like everything was fine. In class, I was hyper-self-conscious and was convinced the faculty was judging my every move. They wanted me to take risks and consider the school a “safe place to fail,” but if I failed too often, they were going to kick me out. And I was sure that being on probation made my fellow students think less of me. It was supposed to be a secret, but word quickly spread about which five of us were on the chopping block.

Teaching actors sometimes enters into a murky territory. Rather than critiquing my acting, I often felt that the faculty was telling me who they thought I should be as a person, some sort of “big, strong woman.” Yet I was 18 and very much a teenager. As a sheltered kid whose mother had monitored her every move, I was experiencing a lot of “firsts.” First serious boyfriend, first time living away from home, and first time riding the subway where I saw (for the first time) someone publicly defecate. I did my best imitation of that confident, take-charge woman they were describing, but it felt so hollow. Still dressed in my mom-approved wardrobe of Gap khakis and sweater sets, I spent my free time reading American Theater Magazine at Barnes & Noble rather than partying at Bungalow 8.

> I did my best imitation of that confident, take-charge woman they were describing, but it felt so hollow.

Thankfully, I fooled them into thinking I was mature. Or maybe I showed enough progress that I was not asked to leave. My last two years at Juilliard were fine, just fine. No one thought much of me as an actor. I remember one teacher saying to another, “Wasn’t she good in that play?” and the response: “Finally.” My big, showy part senior year, which was supposed to show casting directors and agents what I could do, consisted of about four lines. Juilliard had successfully convinced me I was terrible onstage, so I decided to pursue film and television work after graduation. That distinguished me from some of my classmates who seemed determined to pursue a life in the theater. When I was in school, film and especially TV were viewed as the crass, commercial cousins of classical theater. I did notice, however, that whenever an alumnus achieved success on TV, their picture would quietly go up in the lobby.

I gritted my teeth and grimaced each time a teacher told me, “See what good probation did you?”

I’d nod and say under my breath, “Fuck you.” All their criticisms were probably correct. I did have terrible posture, I did need to show more initiative, I did need to lose the Pittsburgh accent. But they’d forgotten to tell me what my strengths were. The one time I brought in a funny scene to my acting class, I got, for the first time, an enthusiastic, positive reaction from my classmates. They’d never reacted this favorably to any scene I’d done before. Instead of encouraging me to pursue comedy or praising my newly revealed skill, the teacher said dismissively, “You can clearly do that. Never bring in a scene like that again.”

I’d started school with little technique but such enthusiasm for the theater. Now all that joy was gone, and I really questioned why I wanted to be an actor. I’d had vague childhood dreams of becoming a judge, book editor, or historian but felt it was now too late to pursue another career. I had no real education, and my scared brain told me I was stuck being an actor. After college, I started auditioning and built my self-esteem back up through therapy and working with people who believed in me and my talent. It wasn’t until I was cast on the TV show Community that I was given the opportunity to do comedy. Working with the cast and writers of that show helped me find the joy and silliness I had lost. After watching several episodes, my friend Joan said, “This is the Gillian I met at 17. You’re back.”

I hate to say I’m grateful for the experience I had at Juilliard. But it taught me several lessons — though I’m pretty sure they’re not the ones the faculty intended. Probation soured my reverence for authority. My need to please others often involved ignoring my inner voice. The more I focus on myself, value my own needs, and work on my shortcomings, the less the opinions of others mean to me. Not everyone is going to like you, and that’s OK. Lately, I find myself muttering, “What other people think of me is none of my business.” And who cared what they thought anyway? Casting directors didn’t call the school and ask, “What did you think of Gillian? How was her voice and speech work sophomore year? Was her neutral mask work strong?” All that mattered was how I did in the audition that day. The pecking order of school was irrelevant once we graduated. In the same way that no one in college cared that I was unpopular in high school, once I left college, I was a blank slate again.

> The more I focus on myself, value my own needs, and work on my shortcomings, the less the opinions of others mean to me. Not everyone is going to like you, and that’s OK.

When I walked into auditions depressed, anxious, and fatalistic, people could sense it. When I walked in calm and confident (even if I was faking it), I put others at ease. Even if I didn’t get the job, I left feeling like I had shown them my best self.

Probation also toughened me up a bit. After four years at Juilliard, I was no longer the coddled teacher’s pet. The life of an actor involves near-constant rejection peppered with the occasional “yes.” I hear “no” all the time, but it doesn’t devastate me because I don’t expect this profession to be easy. Believe me, I get bummed out, but I allow myself to grieve and move on. I watched other students who had an easy time at school really struggle with the business end of show business.

A few years after I graduated, the school abolished the probation system, I’m happy to report. Today, I still crave the good opinions of others and feel a great deal of anxiety when I think I’ve disappointed someone. But I’ve made progress. I’ve realized that no one expects me to be perfect but me, and I try to be kinder to myself. My mom and I have made great strides in our relationship. In fact, working on this piece sparked some really honest and cathartic conversations. When I bottle my feelings up inside, they grow louder in the echo chamber of my mind, but when I force myself to say, “I’m afraid,” they dissipate as others say, “Me too.”

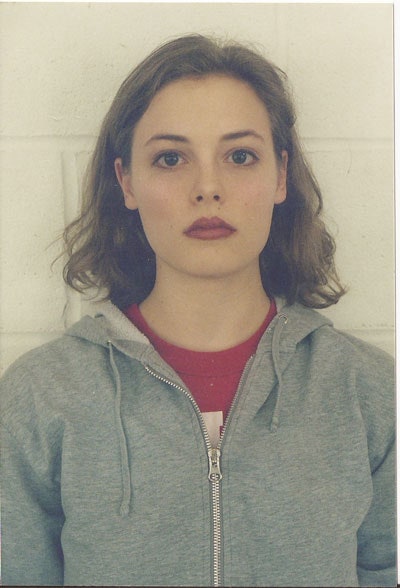

*Gillian Jacobs is an actress (the forthcoming Netflix original series* Love*) and director (the documentary* The Queen of Code *on fivethirtyeight.com)*