It was on the last morning of a trip that my childhood friends made from Houston to visit me in Washington, D.C., that I was introduced to the competitive-dance reality series * (8)* on Lifetime. The four of us skipped brunch and camped out in my living room, eating guacamole and binge-watching the first season. I’d considered myself a bystander to the drama unfolding on the screen, mindlessly tuning in and just biding my time until my hangover subsided. But by the end of the first episode, I was pulling the hair from my scalp and yelling alongside the over-the-top stage moms, who were always being shady in their confessionals. I found myself moving my couch so I could have enough space to better mimic the girls’ dance moves. I found myself praying for Crystianna to (2) her heart out.

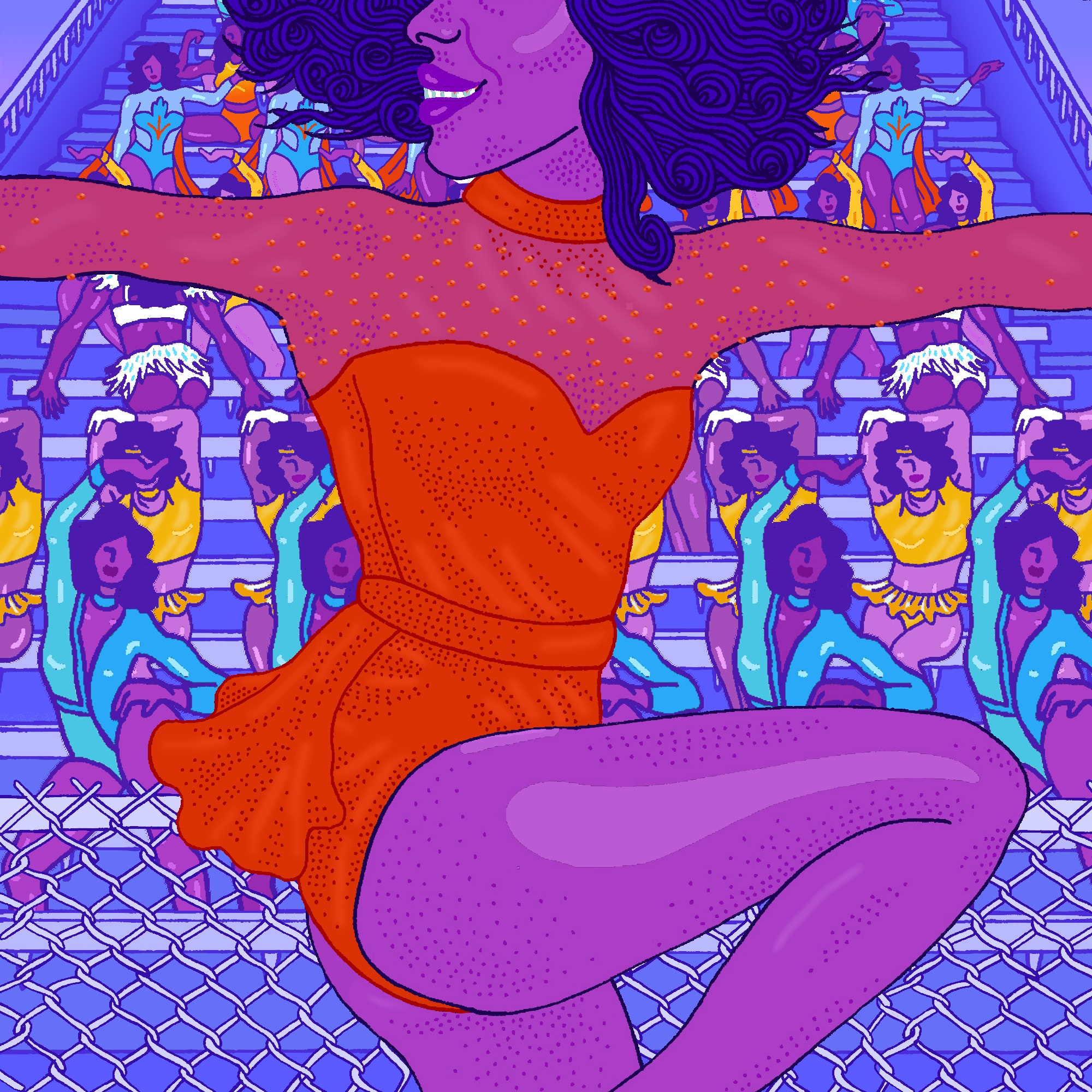

The show gives a glimpse into the epic wins and rare losses of the Dancing Dolls of Jackson, Mississippi, a young, all-black girl’s dance team named after the Dancing Dolls of Southern University, and follows their intense practices every week and competitive-dance performances each weekend. The Dolls, and all the other teams they’re up against from across the Black American South, are unapologetically styled in the image of the legendary Historically Black Colleges and Universities majorette lines, and the middle and high schoolers who make up the teams seem to know that with each buck or death drop, there’s more than just a trophy but an important legacy on the line.

From the first dance battle I saw — when Crystianna, one of the younger girls, pulled her heel up into a standing leg stretch and had the unmitigated gall to look down at her nails, as if to say, *How long you got? Because I could do this all day* — I was hooked. It was such a joy to be reminded of the pride, self-confidence, and personal empowerment that the mere image of black majorettes had given to young girls like me growing up in the Black South. The Dancing Dolls’ high-energy, tradition-twisting battles had me excited for the future yet stuck on how rich the culture was behind their every eight-count.

***

The Third Ward area of Houston, Texas, where my family moved when I was in the sixth grade, serves as an intersection of black life in the city. It has its own rap, its own landmarks, hallowed grounds, and legends, its own projects, its own mansions, its own golf courses, and a heavy influence of the alumni bases from schools like Prairie View, Grambling, Southern, Tennessee State, and Florida A&M, with Texas Southern University sitting right in the middle.

In southern-HBCU circles like the one I grew up in, there is a prolific use of the phrase “Half time is game time.” It affirms what everyone has known about HBCU sporting events since integration: the marching band is inarguably the best and most important part of the experience. My friends and I came up hearing TSU’s drumline practice for games from our back porches, and we moved through adolescence at the football classics, where we would go from sitting and watching the games with our parents to roaming around the stadium with our friends. HBCU band culture and fan clubs were pervasive, but for me and many others raised in that environment, the music was merely a palette for the featured artists — the dancers whose eight-counts and sequined outfits gave the whole endeavor life.

I can still remember being in elementary school and clamoring up to the guardrail to see PV’s Black Foxes and TSU’s Motion of the Ocean (9) at the Martin Luther King Jr. Day Parade. I copied their dance moves from the sidewalk and swung the long, imaginary ponytail that I wasn’t old enough to wear yet.

They looked like grown-up versions of me, empowered and unafraid, in control of their bodies and compelled to use them as tools for expression. Fueling the spirit of the event and setting the stage for the immense band behind them, they livened the streets of our shared neighborhood. There were so many things I wanted to be growing up, and a majorette at a black college was absolutely one of them.

***

There is something special about the HBCU majorette. She, who has mastered the fine art of pinning a full set of tracks into a performance-ready ponytail. She, who has ballerina moves with the swag of (3). She, who over generations has perfected the all-important bleacher routine, aka “stands,” aka “grandstands,” and sees them popping up in music videos all over the world.

Everything they do — from (4) they (5) to the way (6) to the way they (7) — is sculpted and refined in a way that, to me, reflects a desire to celebrate and portray ourselves highly in a world that rarely does. The sequined headpieces that act as crowns, the cutouts in the leggings that embrace, not hide, large thighs, the capes that add an extra side of drama just because.

More than a dance team, they are a force, a movement, a subculture that was shaped, fashioned, and formed by and for black women (though a whole subsect of black gay men has adopted it as well). Previously defined solely by the twirling batons and drum-major-type uniforms, in the hands of black women, majorette has been transformed and expanded to an artistic style of its own, whose routines sing just as loudly as the instruments blaring behind them.

The most important evolution in black majorette dancing is the “grandstand,” which was first put into motion in 1970 by Shirley Middleton, a former member of the Prancing Jaycettes (1)) at Jackson State University who led the charge for majorettes to take more control over the way they presented themselves. They dropped the batons in order to free themselves up for more flavorful routines, which came to be defined by pop-locking arms and deep pelvic thrusts, complex line formations, (10) and silky athleticism.

Grandstands, or “j-setting,” in particular are a series of eight-counts designed to be executed from the confined space of the bleachers while still managing to have as much visual impact as possible. They have names and personalities of their own, can be started in ripple or in sequence, and though they vary from team to team, they always adhere to the same basic, hip-throwing style. On *Bring It!*, grandstands are saved for the last, magnanimous “stand battle” that ultimately determines the winner at the end of each episode.

For those of us who are initiated, we know that rhythmic pattern when we see it and get hype each time we do like we’ve never seen it before. We got hype when Beyoncé first went full HBCU majorette in her choreography for “Single Ladies,” and more recently during her epic Coachella performance this month; my younger sister and I would get hype every time we saw Zoe Saldana and her comrades flash on the screen in *Drumline*; and I stanned for the Dancing Dolls when *Bring It!* came on my television screen each week.

***

My mom still likes to tell the story of the comical shock on everyone’s face when I announced that I would be trying out for Lionettes — the celebrated majorette dance team for the beloved, predominantly black Jack Yates, aka Third Ward High School. For years, I had been fondly thought of as stiff — one of those “tragic cases” of a black girl with no rhythm, too quiet or shy to want to perform during half time at a Friday-night football game; or people thought that I wasn’t “the kind of girl” who would be interested in leotards and sequined shorts. And even though I was many of those things, I was also so much more than they or even I could imagine — so complex, so textured, so layered — and majoretting was one of the many ways I found to express that.

Every time I saw one of the Dolls pop, thrust, and spin into a pique, I was seeing a style of dance that had been perfected by generations of southern, black, HBCU-bred women, being glorified on national television. I was thrilled to be seeing the young girls continue something with such a rich history of black female empowerment, and it made me grateful for the little systems of affirmation that black women have put in place for one another and sustained from one generation to the next. Beneath my fandom was the hope that they would gain from it as much as me and Beyoncé did.

*Jada F. Smith is a writer in Houston, Texas. Read more of her work at (11).*

1) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CMgNwZbFIks)

2) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RiJ211u_Vzw)

3) (https://youtu.be/_-sIHSzJUJc?t=18s)

4) (https://casualtuesdays.com/)

5) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zFmAuJtcgnw)

6) (currently called the (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OSSbsfYYLZ4)

7) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xAjskNBLgy0)

8) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BrpQskyZpv4)

9) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kHmMc7SFgEM&feature=youtu.be&t=2m13s)

10) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b6Sey1uaJLE&feature=youtu.be&t=14s)

11) (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kHmMc7SFgEM&feature=youtu.be&t=4m40s)