In the summer of 2014, Mexican novelist and essayist Valeria Luiselli was waiting for her green card to be either accepted or denied. In the meantime, she began following a greater immigration crisis. Between October 2013 and June 2014, 80,000 unaccompanied children had been detained at the U.S.-Mexico border. Later, it became known that more than 102,000 children arrived between April 2014 and August 2015, hoping to join family already living in the United States.

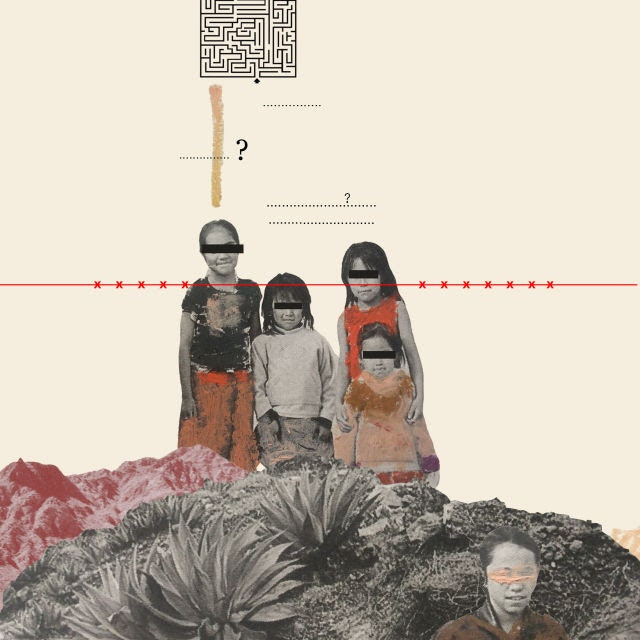

These child migrants journey primarily from the Northern Triangle countries — Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala — facing sexual violence, abduction, forced labor, or even death at the hands of drug cartels on the way. Traveling with “coyotes” paid to take them to the border, they ride on the top of La Bestia, a system of freight trains that travels through Mexico. At the border, they are left in the desert or on the side of the road, hoping to be picked up by immigration authorities, detained, and then sent to their families around the country. Because these children want to become documented residents, turning themselves over to immigration officials is their best hope at receiving (6) (SIJ) or (1), but only if they can find a pro bono lawyer to represent their case.

(13) is Luiselli’s account of volunteering as a Spanish-English interpreter in the New York court system. Faced with this surge of child migrants, the (2) to accelerate their processing, leaving children with just 21 days to find a lawyer and build a case before being deported. Nonprofits such as (14) responded to this crisis by screening children: those with strong cases were matched with lawyers, though many more were deported before they ever made it to court, again facing mental and physical abuse, coercion from gangs, and the extreme violence they were hoping to leave behind.

I first came to Luiselli’s work through her novel * (3)*, the ballad of an eccentric auctioneer who sells, among others, the teeth of Marilyn Monroe. Her work is engrossing, vibrant, and strange, and *Tell Me How It Ends* is no exception. Yet the children’s stories recounted here are not fiction, and she can’t tell you how — or where — they end. We talked on the phone about her experience as an interpreter and the advocacy work she and her students are doing now.

**Monika Zaleska:** In *Tell Me How It Ends*, you describe your role as the “fragile and slippery bridge between the children and the court system.” The children you talk to are sometimes very young but are usually not allowed to have their sponsor or guardian speak for them. Sometimes, they don’t know the answers to the questions you pose, or their answers are fragmentary or incomplete: they don’t know how long they’ve been traveling, or where they crossed the border. I was thinking about this tension in the book between the desire to create an immigration narrative and the idea that it’s almost impossible.

**VL:** The ethical dilemma is knowing that you’re not getting the answers that you need to convince a pro bono lawyer to take on a case. If a case has no chance of getting won, it’s a waste of time for the lawyer. The temptation is to tilt the questions in a certain way, or bias the questions so that the kid might give you enough information to help them. But you can’t, one has to remain ethical and principled and hope that if you’ve asked enough questions enough times that the kid actually will say something. As far as I understand, most of the kids that have applied for SIJ or asylum with lawyers have gotten what they fought for.

**MZ:** So the biggest hurdle is getting the representation.

**VL:** No doubt.

**MZ:** You draw an important distinction in the book between the U.S. government, who sees the record number of child migrants arriving as a “bureaucratic emergency,” a problem that needs to be fixed, but doesn’t want to acknowledge the emergency situation in the Northern Triangle and its reverberations. I’m thinking of one boy’s story in particular: he was granted SIJ status with his aunt, only to find that the same gangs that killed his best friend in Honduras were harassing him at his new high school in Long Island, New York.

**VL:** There is a failure to acknowledge the crisis as something that is not just bureaucratic, but as a crisis that concerns the social fabric of our whole hemisphere. That failure comes from governments’ greater failure to acknowledge their participation: the American government’s failure to acknowledge their historical participation in the roots of this crisis, as well as the Mexican government’s unwillingness to acknowledge their complete incompetence in the so-called fight against the drug wars.

*Tell Me How It Ends* is not a history book, but I do give a genealogy explaining how American money was pouring into El Salvador to support the military government, which massacred Salvadorans and led to many refugees coming into the U.S. Some of those communities of refugees ended up in LA gang culture, where the gang MS-13 for example, sprouted. They were later deported in the ’90s, and this disseminated all over the continent. I think acknowledging this is not hard for an educated — or even just not cynical — Mexican or American, but it’s harder to get government institutions to acknowledge their role.

**MZ:** Despite the rhetoric surrounding immigration these days, most of the child migrants entering the U.S. are not Mexican. In fact, the only children that are deported without being allowed to contact family or receive a formal hearing are Mexican, yet we so often associate “illegal immigration” with people coming from Mexico, without interrogating where these migrants are actually from.

**VL:** Mexican children are not eligible for that I describe in the book, or very few of them are, under very peculiar circumstances. Also, Mexican immigration to the U.S. (15), meaning there’s a lot more people returning to Mexico than coming in to the U.S. So it’s a great misconception, the idea that Mexicans are “pouring in” through the borders.

**MZ:** You write of people protesting the arrival of these children along the border, holding signs that say things like “Return to Sender,” and then wonder “if the reactions would be different were all these children of a lighter color.” You also write of your daughter painting her face white and then coming to you and saying, “Look, Mamma, now I’m getting ready for when Trump is president. So they won’t know we’re Mexicans.” Could you speak directly on the role of racism in immigration now?

**VL:** It’s the elephant in the room with immigration. But there’s less silence around the issue now that the Trump administration has targeted Mexicans, Central Americans, and Muslims. My feeling is that immigrants that are targeted most violently for their race are the Arabs, Central Americans, and Mexican Mestizo and indigenous peoples. I do often think people would have more empathy, would want to help more, if the children were not Mestizo and indigenous. all of a sudden it became incredibly clear how so many people in this country despised Mexicans for being Mexican, for being brown.

**MZ:** You work with the group (4) with your students at Hofstra. I wonder if there are any other organizations in addition to TIIA that you’ve encountered or worked with that you might let us know about.

**VL:** There’s (14) and (11) in Manhattan, and nationally there’s (7) (Kids in Need of Defense) and the (5). All of them are doing fantastic work.

*Writer’s note: Since Luiselli wrote* Tell Me How It Ends, *she has received her green card and is now, in the dystopian rhetoric of immigration, a “resident alien” along with the rest of her family. However, the situation for migrants has become all the more precarious. Stricter surveillance by the Mexican government, (8), has made old passages to the border unpassable, and migrants are taking even riskier routes through the waters of the Pacific. Many hoping to leave behind violence in their home countries (12) under the Trump administration, and many more fleeing persecution have abandoned the idea of a future in the United States, hoping, instead, (9).*

*This interview has been edited and condensed.*

* (10) is a writer, translator, and MFA candidate at Brooklyn College. She is the fiction editor of* The Brooklyn Review, *as well as a contributor to* Electric Literature, Lit Hub, Sweet, *and* Rookie.

1) (https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/refugees-asylum/asylum/minor-children-applying-asylum-themselves?src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

2) (https://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/15/nyregion/in-court-children-lead-line-of-migrants.html?src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

3) (https://coffeehousepress.org/products/the-story-of-my-teeth)

4) (https://hofstra.campuslabs.com/engage/organization/NA?src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

5) (https://www.theyoungcenter.org/?src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

6) (https://www.uscis.gov/green-card/sij)

7) (https://supportkind.org/?src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

8) (http://inthesetimes.com/article/17916/how-the-u.s.-solved-the-central-american-migrant-crisis?src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

9) (https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/03/13/the-underground-railroad-for-refugees?mbid=social_instagram&utm_campaign=likeshopme&utm_medium=instagram&utm_source=www.instagram.com%25252Fp%25252FBRWKMTIhTXQ%25252F&utm_content=www.instagram.com%25252Fp%25252FBRWKMTIhTXQ%25252F&src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

10) (https://twitter.com/myszka_mz?src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

11) (https://www.safepassageproject.org/?src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

12) (https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/07/world/americas/trump-refugee-ban-children-central-america.html?_r=0&src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

13) (https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1566894956/ref=as_li_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=lennyletter-20&camp=1789&creative=9325&linkCode=as2&creativeASIN=1566894956&linkId=3f53d6889846b263a5046a4547498c79&src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

14) (https://www.door.org/?src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)

15) (http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/03/02/what-we-know-about-illegal-immigration-from-mexico/?src=nl&mag=LEN&list=nl_LEN_news&date=060617)