In his eulogy for Reverend Clementa Pinckney, one of the nine individuals killed in the Charleston massacre last year, President Obama affirmed that taking down the Confederate flag on South Carolina’s state capitol “would be one step in an honest accounting of America’s history. A modest but meaningful balm for so many unhealed wounds.” The next day, Black activist Bree Newsome scaled the statehouse flagpole to remove the flag herself. By the time she made it to the top, the pole was flanked by cops, who arrested her upon her descent. She was charged with defacing a monument. Newsome later explained her action, saying: “Every day that flag is up there is an endorsement of hate.” A month later, the South Carolina House voted to remove the flag, but the charges against Newsome were not dropped.

Confederate-flag enthusiasts claim it is simply a way of honoring the valor of Confederate soldiers, an expression of Southern pride. But in Columbia, as elsewhere in the South, the capitol’s flag was not actually a holdover from the end of the Civil War. South Carolina’s governor erected the flag in 1962 to protest desegregation and the civil-rights movement. In effect, the Confederate flag was strategically planted as an endorsement of institutional racism precisely when such institutions were being threatened.

“It wouldn’t be crazy not to want to go to Alabama, or Mississippi, or Georgia, or America,” says Bryan Stevenson, lawyer, professor, and founder of the Equal Justice Institute (EJI), a legal nonprofit based in Montgomery. “I’ve lived in Alabama for 30 years, and I still feel anxiety and doubt and insecurity living in that state. I am very worried about being victimized and injured and attacked and menaced because I am Black.” Stevenson is deeply invested in thinking about how the United States remembers and symbolizes its history of racism. He is one of the country’s most active advocates for the construction of memorials to victims of slavery and lynching.

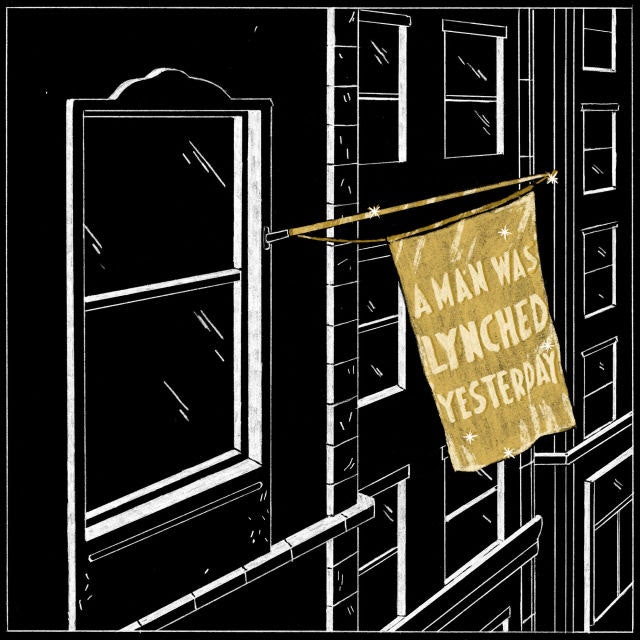

In February of 2015, the EJI published ” (6).” The report documents the history of “racial terror lynching” in a dozen Southern states between 1877 and 1950, and notes that “no prominent memorial or monument commemorates the thousands of African Americans who were lynched in America.” In a response to the report, the *New York Times* editorial board (7) must be integrated into the national conversation about America’s past and present. The board endorsed the EJI’s call to construct memorials for the victims of racial lynching as an essential part of the work of acknowledgment.

This past December, in Brighton, Alabama, the EJI raised a memorial for William Miller. A white mob lynched Mr. Miller in 1908. He was a coal miner and a union organizer blamed for the bombing of his boss’s home (the explosion was in fact set off by whites trying to undermine unionization). The memorial sits near City Hall, recognizing one of the many mostly forgotten and unrecognized victims of lynching and testifying to an American practice and legacy.

At present, there are about a dozen such lynching memorials across the country which were built independently of the EJI. But the EJI’s aim is to organize a coordinated national effort to ensure not only that all victims are remembered, but also that America as a whole comes to understand its history. The memorials are meant to function as a partial remedy to what Stevenson calls the “complete absence of awareness and understanding — just total ignorance — about the legacies of slavery.” The Brighton memorial to William Miller is the EJI’s first official lynching marker, and there are six others currently in the works. To do justice to every person who was lynched, the EJI will have to erect nearly 4,000 more.

|||

Courtesy of EJI.org

|||

Memorialization is an American tradition. In her book * (8)*, American-studies professor Erika Doss describes the memorial mania phenomenon as: “an obsession with issues of memory and history and an urgent desire to express and claim those issues in visibly public contexts.” There are national memorials to the first and second World Wars, and to Vietnam and Korean War veterans. There is a Martin Luther King Jr. memorial, and there is the Emancipation Memorial: built in 1876, funded entirely by freed slaves, with its design overseen entirely by white people, the bronze sculpture shows Lincoln standing and gazing down at a Black man crouching at his feet. There is also the Confederate Memorial in Arlington National Cemetery, which commemorates the Confederate soldiers who died fighting in the Civil War.

But there is no national memorial to slavery, and there is no national memorial for victims of lynching. This is truly staggering, and yet there is little collective sense of outrage. It is certainly not part of the national conversation.

“America a post-genocidal nation that has never owned up to this fact or to the narrative of racial difference that we created,” says Stevenson. “We were never motivated to address the narrative created through slavery, because we were never ashamed.” Shame does not come easy for anyone or any nation. But, Stevenson thinks, “we’ve done a very poor job in this country confronting our failures. The American psyche is built on success and triumph. We’ve come to associate apology or acknowledgment of failure with disloyalty.” While the 13th Amendment abolished slavery, the country never directly addressed or apologized for the narrative of racial difference that supported it.

The EJI is currently working with town and city councils to build its markers, all of which would be simple, relatively small, and specific to each individual victim. The memorials are small bronze plaques, with the victim’s story written in raised gold. Rather than placing such memorials in a special, marked-off area — like the National Mall — these memorials would be integrated into our everyday world. “With the memorials,” says Stevenson, “our objective is really to create a different landscape, where every community that experienced a lynching has to own up to that.”

***

In response to increasing public attention on the police treatment and killings of Black people, (1), (2), (3) (4) have argued that police brutality needs to be understood through the lens of lynching. In a recent interview in * (5)*, poet Claudia Rankine said of the spectacle of Mike Brown’s death: “The sort of execution-style shooting takes it to this whole other place that starts approaching the language of lynching, and public lynching, and bodies in the street that people are walking around.” In a similar vein, philosopher Judith Butler wrote about our “racially saturated field of visibility” in her analysis of the footage of the beating of Rodney King.

For Rankine and Butler, lynching and racism need to be conceived not just as acts or ideas, but as a way of seeing the world and a language for making sense of it. This language is part of what make it possible for trained police officers to see 18-year-old Mike Brown as a “demon,” or to make the split-second judgment that 12-year-old Tamir Rice was a threat grave enough to require shooting bullets into his small, child’s torso. They make it possible for a grand jury to see no reason to bring such killings to trial.

Consider some of the common reasons given for a lynching at the turn of the century and through the 1960’s, social transgressions so minor and unpredictable as to be practically unavoidable: being obnoxious, acting suspiciously, arguing with or insulting a white man, living with a white woman, race troubles, unpopularity, demanding respect. Consider some of the circumstances that led to someone getting killed in recent years: selling loose cigarettes, broken taillight, shoplifting cigarillos, knocking on a door seeking help with car trouble, mental-health crisis, playing with a toy in the park.

***

For Stevenson, video footage of police killings is crucial for cultivating white people’s capacity to see the police as a force of racial oppression forged by postbellum policy. But he also sees a risk. As he points out, “we’ve accommodated ourselves to seeing violence on screens without being burdened by it.”

Just as the killings can be understood as a new form of lynching, so too can the interest in watching be seen as a new version of the documenting and distributing of images of lynching at the beginning of the 20th century. Lynchings have always been spectacles. In response to news stations that played and replayed the police shooting of Walter Scott, professor Britney Cooper wrote in (1), “Black folks are being treated to an endless replay of this murder on cable news. There is no collective sense that being inundated with video and imagery of these racialized murders of Black men by the police might traumatize and re-traumatize Black people who have yet another body to add to a pile of bodies. Black death has become a cultural spectacle.”

By insisting that we remember the history of lynching and let it inform our sense of the present, lynching memorials and other practices of remembrance would cultivate the much-needed collective experience of being burdened by these images. But without such sense of burden and historical understanding, images of racialized murders will not disrupt but will instead simply circulate.

***

Stevenson often compares America’s discomfort with the memory of its mistakes to other countries’ efforts to bear witness to their brutal histories. He sees South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission as one model for collective reckoning with the moral failures of the past; he sees Germany’s commitment to memorialization as another. “In Germany, swastikas are illegal. There are memorials everywhere. You are almost required to encounter the legacy of the Holocaust.”

Memorials intervene in the world. They interrupt movement. They reroute our thoughts and bulldoze our feelings. They change what we remember, what we celebrate, how and what we see. Of course, they can also be seen as cheap gestures facilitating collective self-congratulation and the cessation of real social change. But as Bree Newsome recognized, flags and memorials are not *merely* symbolic or ornamental; they are *fully* symbolic, the shared symbols by which we make sense of the past and the present. The Confederate flag functions as one such symbol, and a lynching memorial stands as another. When done well, memorials can function as the basic units for a counter-narrative, for a new way into the world.

Memorials transform the landscape. But the EJI is also working to preserve part of that landscape. Besides the markers, the EJI is also engaged in an archival project of collecting soil from every location where a person was lynched in the state of Alabama. The EJI and volunteers take some earth from these sites and place it in jars labeled with the names of the victims. Both the markers and the soil-collection project acknowledge that the past is buried in us. It’s shaped this land, sits on the surface of the earth, and runs deep in the ground.

Memorials guarantee nothing in terms of our shared future, and they will never eradicate the tendency to careen toward forgetfulness with respect to the past. But they have the power to trouble that tendency and disrupt our habits. With these markers, the past arches up to meet us, and in the same moment we are confronted with a new understanding of the present and a new sense of ourselves. But only if we are willing, only if we shift some of the burden, and change the way we bear it.

*Francey Russell writes about art and film and is a PhD candidate in philosophy.*

1) (https://www.amazon.com/Memorial-Mania-Public-Feeling-America/dp/0226159418)

2) (https://www.salon.com/2015/04/08/black_death_has_become_a_cultural_spectacle_why_the_walter_scott_tragedy_wont_change_white_americas_mind/)

3) (https://www.huffingtonpost.com/jerome-karabel/police-killings-lynchings-capital-punishment_b_8462778.html)

4) (https://www.dailydot.com/via/black-men-police-violence-lynching-internet/)

5) (https://www.dailykos.com/stories/2014/11/13/1344670/-5-ugly-and-uncanny-parallels-between-lynchings-and-police-killings-in-America)

6) (https://www.newyorker.com/books/page-turner/seen-interview-claudia-rankine-ferguson)

7) (https://www.eji.org/reports/lynching-in-america)

8) (https://www.nytimes.com/2015/02/11/opinion/lynching-as-racial-terrorism.html)