The ritual bath was housed in the back of my parents’ Orthodox synagogue, with a separate entrance to ensure privacy. Inside, there was a bathroom with a shower and tub, and in an adjacent room, the small pool — a _mikvah_ — with enough space for one person to stand with her arms outstretched. Above was a large round opening in the wall through which the attendant could watch and ensure that every part of the woman was fully under the water.

“Are you excited? Are you nervous?” my mother asked me as we walked in, a few nights before my wedding.

“Both,” I admitted.

As a bride, I was required to immerse myself in order to be sexually permissible to my husband. As a wife, I would be required to do this every month.

In preparation, I’d soaked in a tub, cut my nails, scrubbed my calluses. I forced a comb through my thick hair. The comb ripped out so many strands, but I wanted to follow the laws precisely.

In the months prior, I’d been studying the religious laws that would now apply to me, sitting around the dining-room table of a rabbi’s wife.

“This is beautiful,” she told me and the dozen other engaged young women, about the rules of Jewish family purity. When we had our periods and for the seven days following, we were in a state of impurity: We couldn’t touch our husbands — no sex, not a hug, not a handshake. Once our periods had ceased, we were to check ourselves for any remaining smudges or stains. When we believed ourselves to be clean, we were to leave the cloths inside ourselves for 30 minutes, just to be sure, and then start counting seven clean days. Only at the end of these could we immerse in the mikvah and once again be permissible.

In high school, equally strict rules of modesty had touched down on my body: safety pins were kept in the office to fasten shut a low-cut blouse or a skirt with an offending slit. Mothers were called if a new skirt needed to be procured; a spare skirt was kept in the office for those times when a mother wasn’t reachable. Our knees, elbows, and hair were discussed in black-scripted rabbinic texts, featured prominently in the school rules, in notes sent home reporting infractions. We were always subject to inspection, our bodies divided and measured. The rules were written across my body, mapped onto my skin, my hair, my thighs. Now that I was getting married, they were poised to enter my body as well.

_You don’t have to feel that way,_ I chided myself whenever I felt a slow burn of resistance. Contrary to how it might appear, this was not an invasion of the most private sphere of my body. This was not an issue of a woman being deemed impure. Shape it and twist it, change it and smooth it — some sort of machine inside my head, skilled at reprocessing and reconfiguring any torn bits into a smooth whole in whose billowing folds I could still seek comfort. Quibble, if necessary, with some of the details, parse the interpretations, summon various rabbinic figures for support — anything to prevent my body from whispering a small silent _no._

I called the mikvah attendant so she could check me for any dangling cuticles or stray hairs that would constitute a separation between my body and the waters.

“I’m ready,” I told her.

I descended the steps. Here was the portal to adult life.

***

I went to the mikvah every month of my marriage.

“This is beautiful,” I still told myself, but when I got to the mikvah, all I wanted to do was get in and out as quickly as possible.

It didn’t matter how I felt about the rules, just as long as I followed them. I wanted to remain Orthodox, at all costs. Sometimes, in synagogue, I noticed that I stood with my arms folded across my chest, my fingers tightly digging into my arms as though I needed to hold myself intact. But even so, I was Orthodox, even though I sometimes doubted. It seemed less a statement of what I believed than a truth of who I was — its language, its rhythms, its customs, all part of me. Its weaknesses, its battlegrounds, its shortcomings, part of me as well.

Once I completed the required preparations, the mikvah attendant examined my nails for any remnants of polish. She checked that my toenails had been clipped and scrubbed. Everywhere you went, you were supposed to be covered, yet as an Orthodox woman, you were always subject to inspection.

“Can you comb your hair a little better?” she asked me one time.

I was surprised — she’d never before said much to me, only picked a few hairs off my back or motioned to a hangnail I needed to snip.

> I was in this lake not to purify myself but to open myself as wide as I could be.

I went back into the bathroom, held the comb to my hair, and looked in the mirror, feeling as though I’d been tasked with subduing the most resistant parts of myself.

_Do you believe in it?_ I asked myself, a question I tried to avoid.

I looked at my hair. I wasn’t going to comb it again.

“I can’t,” I told the attendant when I emerged from the room again.

She raised her eyebrows in confusion.

“I can’t,” I said again. Nothing in my life had felt as certain as that one sentence.

With a small, perturbed shake of her head, she quickly inspected the rest of my body. Maybe she saw the resoluteness in my eyes. Maybe she was calculating that the sin would be on my ledger, not hers. Maybe I would be inspected more thoroughly in the future, the mikvah equivalent of a no-fly list.

With resigned approval, she watched as I went under the water, my fists loosely clenched, my eyes lightly closed. I felt pinned in place like the bugs in the collection I’d had to amass for my sixth-grade science class. I’d caught spiders and beetles and moths in a glass jar and placed a cotton ball soaked with nail-polish remover inside. I’d watched, horrified and fascinated, as they flittered and scurried then slowed, their legs no longer moving, their wings no longer flapping. When they were dead, I carefully emptied them onto a Styrofoam board and stuck a pin through each hard body.

“Kosher,” she pronounced. “Kosher.”

***

I couldn’t go back. At the thought of it, my chest tightened, as though my ribs were curling, each into a small silent _no_ .

But I couldn’t not go either — the wheels of my marriage would have ground to a halt. Without the mikvah, there could be no sex. And without shared observance, I couldn’t imagine how we would exist together. My husband and I had signed a marriage contract, but another contract existed between us, equally binding and unchangeable, in which we agreed that we would always be Orthodox.

As a compromise, I started going to a non-Orthodox mikvah, whose mission was to reinvent this ritual. Instead of inspecting me, the mikvah guide dimmed the lights and asked me how she could help make my experience more meaningful.

But I felt closed to the experience. I wasn’t here in search of a meaningful ritual — I was here because I had to be, here to submit my body to rules, even if I didn’t necessarily believe in them.

A few years later, a friend from our synagogue called me. “Do you want to do something a little crazy?” she asked.

To my surprise, she wanted me to go with her to a nearby lake and be the equivalent of the mikvah attendant as she immersed. Like me, she could no longer bring herself to go to the Orthodox mikvah where she usually went.

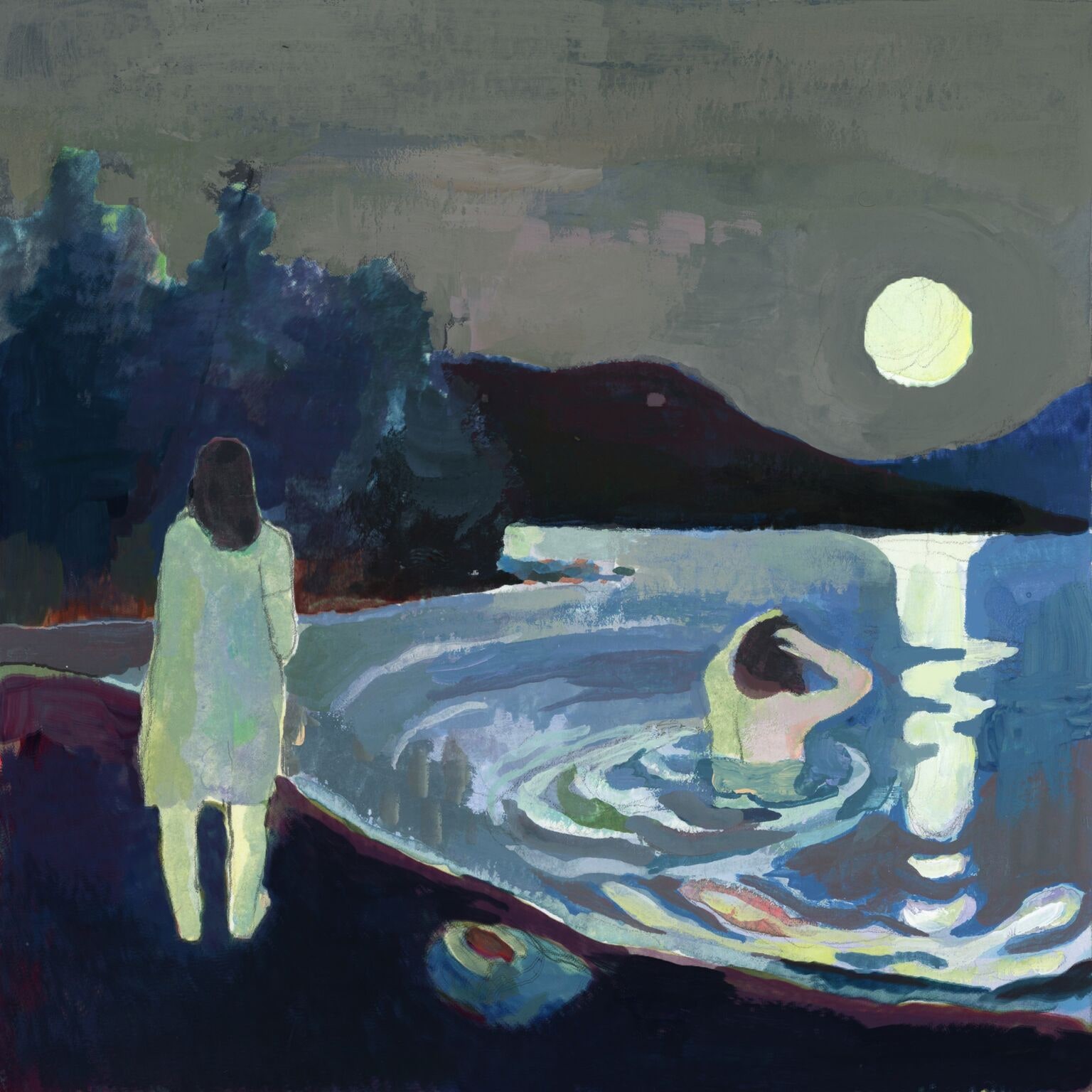

It was nighttime when we went to the lake, and I could barely see my friend as she walked out into the water, wriggled out of her bathing suit, and went under. She had complied with the rules but also found a way around them. When I got home that night, I wondered how much longer I could continue to do that as well. I lay awake, thinking about street performers I’d seen a few months before who’d folded themselves, arms over legs over necks, into smaller and smaller glass boxes: seemingly impossible feats, but I knew all too well the feeling of having to contort yourself to fit inside.

The next month, when it was time for me to go to the mikvah, I instead went to the lake. With my friend standing by the edge of the water, I waded out, slipped off my bathing suit, and went under.

Alone in the water, my body made ripples that floated across the still surface. I lay on my back, took in the moon, which was low and full, and the sky lit with stars. I felt some softness and easing in my body, some relaxing of my always-compressed state. If there had been any sliver of meaning for me, it lay in the feeling of being away from the rules, away from the official eyes.

In the end, when I left both the rules of Orthodox Judaism and my marriage, I remembered this feeling. The urge to leave had started to feel like a physical rising from inside. _No,_ every part of me knew. _No,_ I wasn’t willing to live in accordance with the rules, and _no,_ I didn’t believe, really believe, the rules contained the ultimate truth, and _no,_ I couldn’t keep trying to tuck away this feeling, and _no,_ I could no longer follow without believing.

The next time I was in a lake, after I’d left, I swam far out into the water, where I floated on my back, staring up at the sky domed above me and the trees circling all around. In the absence of the rules, my life felt as unmappable as the water I was in. But inside my chest, there was now a widened, no-longer-knotted feeling, as though more space had been created between my ribs. I was in this lake not to purify myself but to open myself as wide as I could be.

*Tova Mirvis is the author of* (1), *a memoir, and three novels:* (2), (3), *and* (4), *and her essays have appeared in various publications, including the* New York Times, Real Simple, *and* Poets and Writers.

1) (https://www.amazon.com/Book-Separation-Tova-Mirvis/dp/0544520521)

2) (https://www.amazon.com/Visible-City-Tova-Mirvis/dp/0544047745)

3) (https://www.amazon.com/Outside-World-Vintage-Contemporaries-ebook/dp/B000XUADLS/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1505482673&sr=1-1&keywords=The+Outside+World)

4) (https://www.amazon.com/Ladies-Auxiliary-Novel-Tova-Mirvis-ebook/dp/B004H4X85E/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1505482688&sr=1-1&keywords=The+Ladies+Auxiliary)