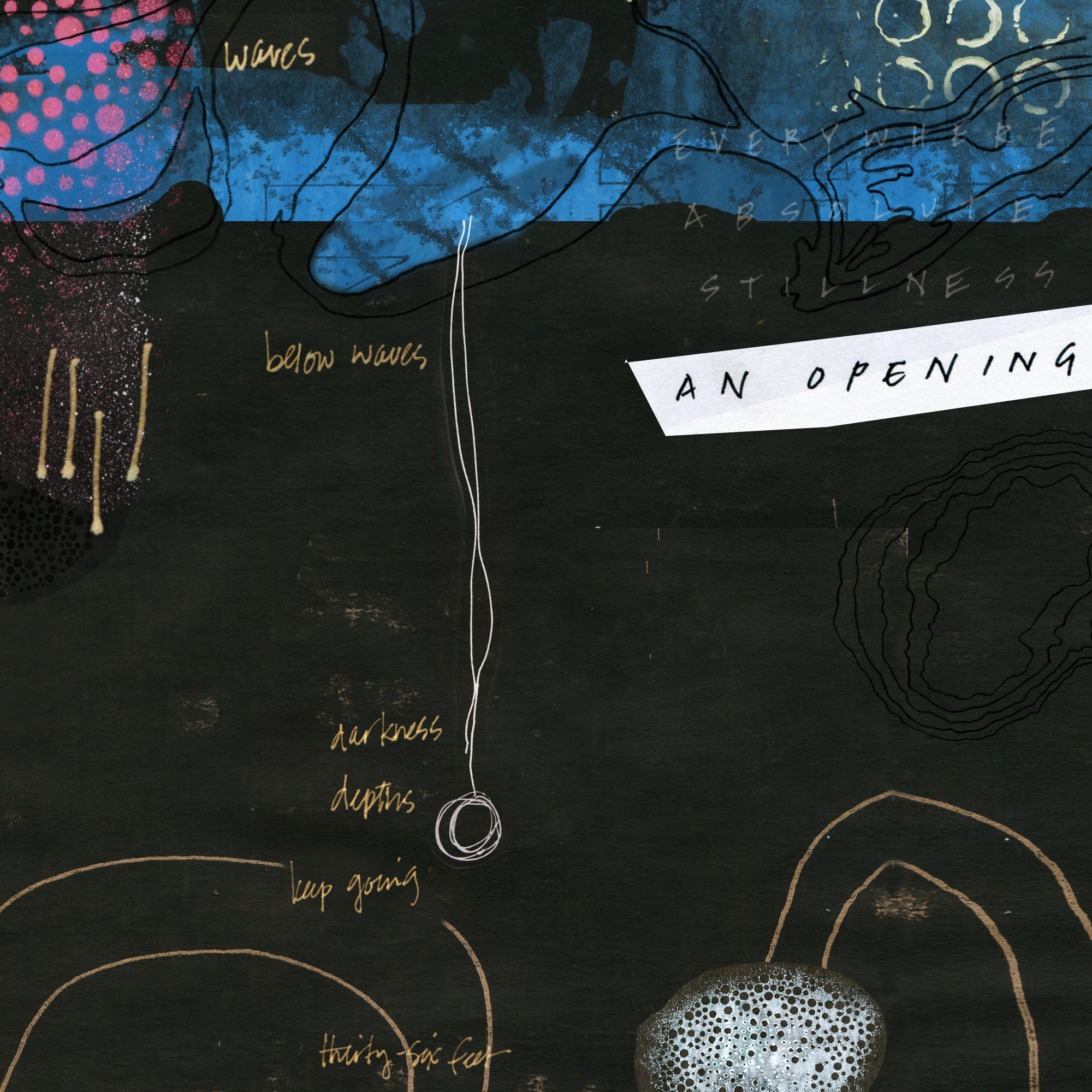

Eighty-nine years ago, Else Bostelmann descended 36 feet below the turquoise waters off a Bermudan shore with a makeshift easel and a set of oil paints. She was wearing an “unusual bathing outfit” — a metal helmet, for seeing and breathing underwater, and a red bathing suit. Bostelmann tethered her paintbrushes to her palette to ensure they wouldn’t float away, the playful currents frustrating the artist’s work. She had entered a bustling new world of moods and shadows, of gilled, unfamiliar faces and neon corals, and now she would paint them. Later, she would note a contradiction she observed while underwater: “everywhere absolute stillness — yet ceaseless activity.”

|||Saber-toothed viper fish (Chauliodus sloanei) chasing ocean sunfish (Mola mola) larva, watercolor on paper (1934).|||

Bostelmann, born in 1882 in Germany, and later classically trained as an artist, had joined the Department of Tropical Research (DTR) by way of New York, where she was recovering from her husband’s mysterious roadside death in Arizona. Looking for work, she contacted Dr. William Beebe, founder of the DTR and leader of its missions to Central America and other tropical locations, like the Galápagos Islands and Bermuda. Beebe, impressed by Bostelmann’s artwork, took her on; soon, she was on a research vessel off the waters of Bermuda. It was 1929, and Bostelmann was 47 years old.

Aboard the *Arcturus*, Beebe facilitated a spirited environment. He threw costume parties on the boat for scientists and artists alike, but Beebe’s expeditions were notorious for another reason — they often consisted of women in positions of scientific and, in the case of Bostelmann, artistic authority. Beebe was running one of the most influential research departments in the United States, and women were at the forefront, contributing research-based results and illustrations to the DTR’s massive output. Some of the other women aboard included Jocelyn Crane, whose work defined a generation of information on the fiddler crab, as well as scientist and naturalist Gloria Hollister. Several talented artists were also paramount to the operation’s successes — Anna Taylor, Isabelle Cooper, Helen Tee-Van, and, of course, Bostelmann. Without underwater cameras, these women were crucial to the DTR’s cataloguing of specimens.

Popularizing science and bringing it into the mainstream made Beebe a target of skepticism at the time. (His longtime rival, for example, ran a dry operation and banned women from spending the night at his camps as a way to legitimize his research over Beebe’s.) And because Beebe also employed women, critics diminished his work’s seriousness. He was additionally faulted for his playfulness and whimsy. But the DTR’s unique fusion of art and science, and resulting works like Bostelmann’s, had a far reach. For many Americans suffering through the Great Depression, a first look into the deep sea was refreshing, especially as it was through the eyes of the women onboard: though it was a man who created the technology to reach the ocean floor, it was the women of the DTR who brought its life to shore.

|||Bathysphaera intacta, watercolor on paper (1934).|||

And the rigors of their work were not to be discredited. The team worked diligently, gathering samples and taking trips to the bottom of the ocean in Beebe’s bathysphere, a steel ball sized for two humans and designed to explore the ocean floor. From there, Beebe would speak into a small telephone, calling up to an artist on the surface, oftentimes Bostelmann, describing his observations. Following Beebe’s studies, Bostelmann would set to work, rendering animals she had never seen: fish with menacing jaws and odd lamps dangling before their faces — the subjects of nightmares and dreams.

***

Katherine McLeod is a doctoral candidate in the history department at NYU and was one of the curators of a 2017 exhibit about the DTR that ran at the Drawing Center in New York. McLeod specializes in the legacy of the DTR, and as we sat outside a West Village coffee shop discussing the history of exploitative politics of the ecological sciences (and Beebe’s murky politics in general), she helped make some sense of Beebe and the DTR.

Many decisions he made were controversial then but tend to put him above reproach now, like the inclusion of women on his expeditions. However, the application and practice of these decisions deserves a nuanced evaluation: few of the women were paid for their work (though Bostelmann was), and they were sometimes conscripted into domestic and secretarial labor. Further, many of Beebe’s expeditions depended on piggybacking on the infrastructure of colonialism — from roads to clearings to outposts — a fact that today continues to contribute to the complexity of ecological and conservation endeavors, and who actually is the benefactor of these sciences.

|||Chiasmodon niger, watercolor on paper (1931).|||

These politics make an appraisal of Beebe’s mark on our society difficult to calibrate, though one enduring and admirable trait of the DTR’s work was the group’s dedication to outreach. Beebe took pleasure in bringing the ocean to land-dwelling humans, and did so with frequency in articles, lectures, and exhibits, including a whimsical 1939 World’s Fair exhibition, conceived of and curated by Salvador Dalí. Visitors purchased admission from an anglerfish-shaped ticket booth and proceeded through a cave filled with women scantily clad as mermaids. Bostelmann’s illustrations were on prominent display, reaching millions more people via the pages of *National Geographic*, where her distinct style and keen eye for detail intoxicated the magazine’s readers.

McLeod, parsing through Beebe’s varied résumé, put it well as she took a sip of her tea. “There are times when I’ve read Beebe and I’ve thought, *That really is groundbreaking. That really is an opening to something that didn’t exist before,* and I look at paintings … as another one of those openings.”

***

Mid-afternoon on a sleepy, 90-degree Friday, I was lost in the Bronx, looking for the Wildlife Conservation Society archives. Nestled secretively in the inner confines of the Bronx Zoo, the archive holds over 100 years’ worth of WCS records — including a wealth of Bostelmann’s sketches from the DTR’s Bermuda days.

Though Bostelmann would don the helmet from time to time for walks on the ocean floor, her paintings rendered 40 feet below the water’s surface were largely used to inform her work onboard the ship, where she interacted with samples of fish trawled from the ocean. It was in this environment where she was able to focus on the detail that defined her illustrations. “Through the microscope,” Bostelmann wrote, “a new world of undreamed beauty was revealed.”

|||Submerged beach at 1,400 fathoms, watercolor on paper (1931).|||

Here were those illustrations, stained and watermarked from their oceanic genesis, all collected and stored in the basement of a regal building in the Bronx Zoo. I turned the protective film away from a painting of a seahorse giving birth. It looks like a little dragon with its green, dappled tail wrapped tightly around an unfinished reed, holding the animal steady as babies blow out of its stomach as if by a gust of wind. The babies are small, like sea monkeys, and scattered around Bostelmann’s page seemingly caught on a tide, floating away. I snap a picture of the scene, adding my hand for scale, my fingernail capable of fitting about five of Bostelmann’s seahorse babies on its plane.

It goes without saying that Bostelmann must have worked under extreme time constraints and conditions, and made great sacrifices. A widow, Bostelmann had left her teenage daughter back in New York in order to join the DTR on its expeditions. But based on her writing, she loved her work. Describing the stressful moments of capturing a live fish’s essence as it is brought up from the ocean floor, she wrote, “then began the busiest time of my day as I undertook the quick sketching of their fleeting, iridescent hues, their still glowing light organs, the ephemeral brilliancy of their metallic sheen.” She had a relationship with each specimen that extended beyond artist and subject. “Sometimes I let them face me,” she wrote, “and I am astonished at how often they resemble one or another of my friends!”

|||Big bad wolves of an abyssal chamber of horrors, watercolor on paper (1934).|||

Indeed, Bostelmann’s creatures are characters: a stone-eyed silverfish with an underbite of needle teeth like a can opener; a party of indifferent puffers seeking a lunch of snails; a critter with a face like a striped cow and little red fronds growing out of its nostrils; a speckled squid; a red curled shrimp; an anglerfish that looks like it’s yelling at you. Bostelmann’s imagination reaches out, grabs you by the hand, and leads you away from land. The work may seem cartoonish, but I have a theory that the reason Bostelmann’s work is so accessible is *because* it’s so animated. Each fish is relatable, human-like, making the ocean nothing to be afraid of. It was no wonder her work reached so many people who, in the throes of economic depression, needed to escape to a world drastically different from the one unraveling on land.

|||Blue and orange nudibranch, watercolor on paper (1931).|||

Among the pages of squids and hermit crabs was a note on the back of one of Bostelmann’s drawings. “Scales too large. Dorsal rays too few,” it read in cursive scrawl. It was a critique of one of Bostelmann’s renderings — calling out its inaccuracies — by one of the female scientists aboard the ship. Evidence of two women working side by side to perfect the image of a fish for the world to see, a beacon for the future of women in science from a time when the laboratory was a man’s domain. One day, these images would be in the pages of *National Geographic* and eventually find their way to museums and archives, but the immediate problem was the fish and its proportions, and these two women were working on solving it.

*Kea Krause is a freelance writer in New York City.*