When I first decided to strip in the grubby clubs in the Tenderloin, I lived in a tiny square room in a dilapidated Victorian apartment with three other roommates I’d met on Craigslist. My room had a legal-pad-sized window with a view of a drippy gutter. I slept on a borrowed mattress on a dusty hardwood floor.

It was the 1995, pre-tech, perma-fog, home-of–Queer Nation, Food Not Bombs, underground-gay-sex-clubs, needle-exchange San Francisco. I was always moments from getting evicted. Each month, I begged the landlord for one more week, until finally I came home to a note on my door from my roommates asking me to please move out.

I was 25 and scary-broke. I worked minimum wage at a clothing store where I sold my used T-shirts on my lunch break to buy a burrito next door. Most nights I sat in chilly yellow church basements holding hands with other addicts, praying for sobriety, transcendence, and rent control. I’d recently kicked meth and was startlingly alive, even though I was reeling from loss after dozens of my friends had died from AIDS.

My mom knew I’d quit doing the drugs that made me paranoid and skinny because I’d started returning her phone calls again. She also knew about my bisexuality because I’d brought my girlfriend, Austin, home one Christmas. The two of them sat close, sipped whiskey-Cokes, and giggled while Mom’s cheeks turned rosy. “I always thought being bisexual would be the best of both worlds,” she said. She knew I struggled financially and that I was in AA, too, but she didn’t know I’d slinked away from our small town to be a sex worker. Would she be ashamed of me if I told her? Would she stop loving me?

I didn’t grow up poor. Neither my dad nor my brother molested me. I was raised on _Flashdance_ and _Xanadu_ in a cow town with lots of pot growers and churches filled with Republicans. A creek trickled outside my bedroom and the dewy clover glistened like Mom’s Avon Coco Crush lipstick. Shadows were long and quiet — echoes of endless rain.

My pretty, paralegal mom raced around getting ready for work each morning. The minute her blow-dryer stopped, I ran upstairs to watch her curl her wavy brown hair and apply sparkly bronze blush with a greasy round sponge. When I was late, she’d bark, “Pay attention” and “Hurry up.” She pressed a menacing eyelash curler onto her eyelids and counted to ten under her breath, then packed frosty blue eye shadow on top with the ferocity and efficiency of a python swallowing a gerbil. I stood in her fresh Pert-shampoo steam and inhaled. In those moments together, it never occurred to either of us that I’d become a stripper.

***

As a kid, I slugged it out in tap and ballet classes from ages five to fifteen. Dancing onstage anywhere was simply dancing, wasn’t it? The same way a lifelong swimmer seeks refuge in the water — the stage was my habitat. The stripping-as-performance-art aspect of the service industry in San Francisco made sense. I wanted my mom to be proud of me and not worry about me anymore. But every time the subject of work came up, I lied.

I didn’t inherit my mom’s steadfast punctuality, but my heart still races whenever I leave for work, cramming in too many tasks in too short a time, drunk on the circus of unwarranted optimism — panicked to get to my job at the university, restaurant, or strip club. I inherited her preoccupation with having a purpose. For both of us, work is never simply work.

Before she died from cancer, Mom belonged to several women’s organizations. She raised money for underserved schools and bonded with other university women, and she protested corporate-development projects that robbed Northern California of its natural resources. She was pleased when I enrolled in “Black Feminist Thought” and “French Women Writers” classes at Mills College. Could a woman like her support the idea of my doing sex work? Could I?

I knew stripping had selling points other than fast money. I admired feminist artists like Karen Finley and Laurie Anderson, who used their bodies as tools for political change by pouring glitter on their breasts and reciting aggressive monologues about the concept of “dressing up.” To test my theory, first, I shaved off all my hair. Then I marched into the strip clubs determined to take down the patriarchy, one lap dance at a time.

> Could a woman like her support the idea of my doing sex work? Could I?

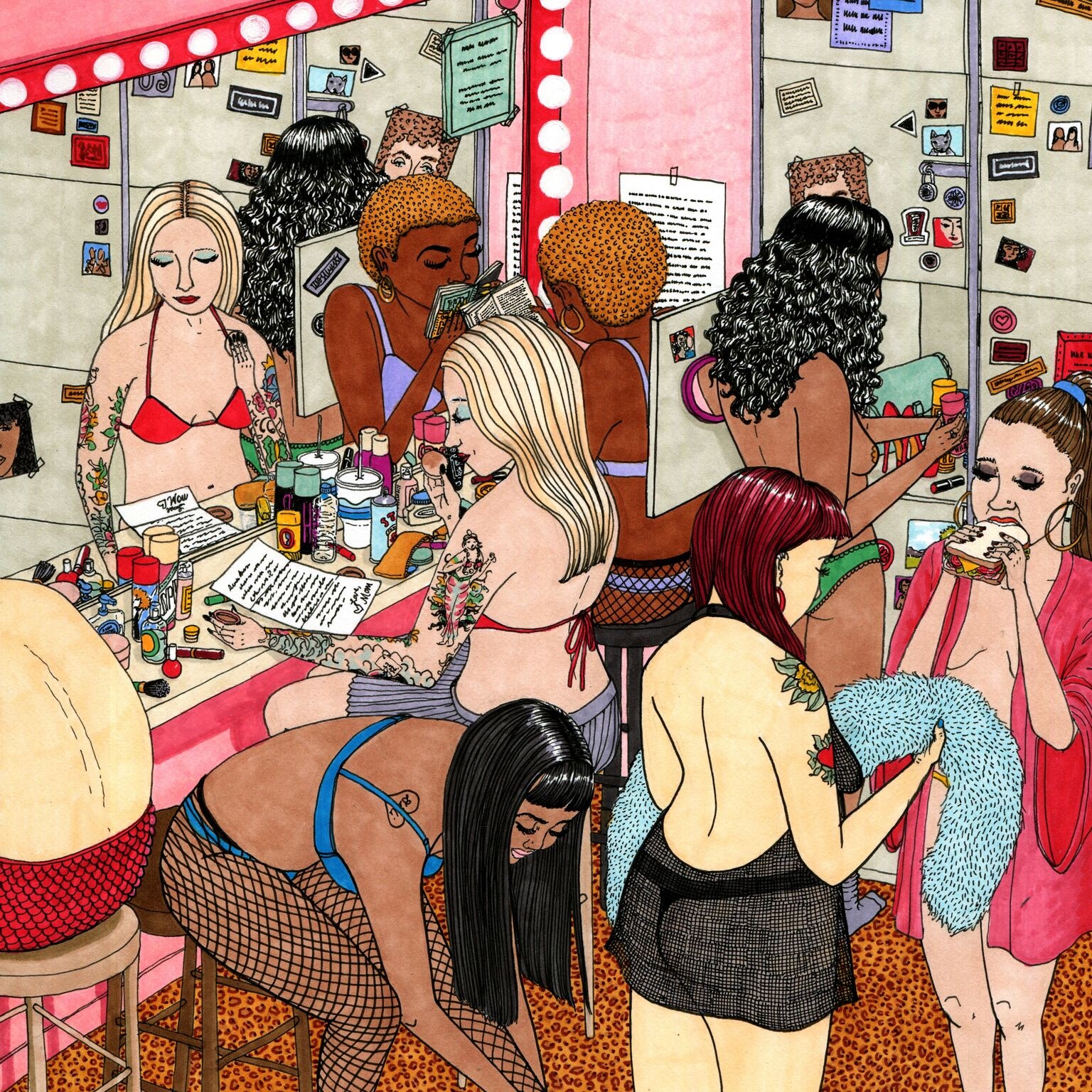

My first night stripping was no feminist manifesto. I fought off fingers in the dark like crabs crawling across my rib cage and watched the women work. A blonde with pinned eyes bumped hips with me and said, “Don’t make a fuss, just get on the bus.” These dancers were not conveyor-belt McStrippers with plastic baby voices. They were athletes who whipped their red braids around and danced in PVC corsets. They moved with aerodynamic strength and flashed their witchy gazes. Great stacks of gifts piled up in the dressing-room corners from their special customers. Some of them had expensive hair and Beverly Hills boobs. Others seemed to have fewer options — single mothers with little education and massive drug habits; teenage runaways with black eyes who whispered, “Do you want to play with the kitty?” Other girls studied textbooks for nursing school or real estate between stage shows. I felt silly and small and fat and cheap and then slowly became a seasoned prowling lap dancer who grew greedier and more alienated with every 4 a.m.

My occupational secret built a stone partition between Mom and me. Even when I enjoyed the fleeting affection and cash from horny strangers, my mom’s love was airtight and unconditional. It smelled like her chocolate sheet cake and her horses. My customers tasted like tequila, Marlboros, and antibacterial gel. I couldn’t imagine telling Mom about the VIP shower room where I peed on a man in an Armani suit for a few hundred bucks then gasped while a freckled redhead named “Faith” danced barefoot to Jimmie Vaughan’s “Dengue Woman.”

I learned the power of the pole and the art of making myself small in large and crusty laps. I was making ten bucks a song, then $40, then $60, then $120 for a hand job behind a black curtain. I splurged on organic peanut butter and platform Mary Janes. I moved out of that shitty apartment, then into another one, where I lived alone and bought a motorcycle. And somewhere in the furious hustle, I missed my mom desperately, even when I buzzed with the thought of _Holy fuck,_ _I should do this always._

_****_

When we talked, Mom asked, “Honey, what are you doing to get by?”

“I get by,” I said. Then, two years into my stripping career, she told me she was coming to visit.

I thought about the Lusty Lady, where I danced nude behind one-way glass. I decided to bring her there.

The Lusty Lady peep show was owned and operated by women. My coworkers were poised and educated, fire-breathing, stilt-walking single mothers, artsy women with confidence and cats. They had savings accounts and skateboards. The Lusty Lady kept us on a schedule. We paid taxes and took five-minute breaks every hour. One day, during my shift, my coworker Sizzlean noticed a blinking red light and discovered that customers were filming us without our knowledge or consent. She asked our show director to take out the one-way glass and ban video cameras. Management refused and told us if we didn’t like it, we could go work somewhere else. Then I found out other things: the black girls got fewer shifts and couldn’t cover a white girl’s shift, and a busty girl had to have another busty girl cover her, not a flat-chested, skinnier girl.

My coworkers were not going to put up with it OR leave, so we decided to organize, even though no other strip club had ever done this before. We wanted basic rights, like the right to cover our shifts, and we wanted the one-way glass removed so customers wouldn’t film us. We held secret meetings. Had a “no pink” day where we covered our pussies. Collected hundreds of signatures from local businesses. Handed out condoms. Picketed. We fought our labor war and won. I stayed clean.

I told my mom about the plight of my all-woman workforce, and she listened intently, sipping a Diet Coke. I explained stripping as plainly as possible: girls dancing shoulder to shoulder together on a stage. “How long have you been stripping?” she asked.

I told her the truth. She nodded.

We walked into the Lusty Lady lobby like any daughter would take her mother into the office to meet her boss and her coworkers. We squeezed into a corner booth and watched the bodies dancing onstage. I pointed and mouthed “my mom” to Star and Decadence. They grinned and waved. I never showed Mom the Private Pleasures booth, where I gave dildo shows for Enema Man and Speculum Man and the gang of Christmas Clowns (there are details even an open-minded mother doesn’t need to know), but I showed Mom that a place normally associated with desecration and exploitation was a place of sisterhood, strength, and self-esteem.

Her daughter was not some broken stripper lost and trapped; she was a member of SEIU Local 790: The Exotic Dancers Union. We daughters were strippers who had support from our city and our community. I was proud. Mom flashed her Dentyne smile and said, “It’s silly. And it looks like fun.”

_Antonia Crane is the author of the memoir_ (1) _(Rare Bird Lit/Barnacle Books, 2014). She is a writer, performer, and instructor in Los Angeles._

1) (https://www.amazon.com/Spent-Memoir-Antonia-Crane/dp/1940207061)