That ol’ expression “Heart of a lion, skin of a rhino, soul of an angel” — it’s the kind of thing that’s scrawled in cursive, pinned to a million Pinterest boards, immortalized in needlepoint. It seems banal until it’s applied to this collective of women, and then it’s a revelation, prophetic.

Meet (3), the all-women conservation unit that’s turned the bon mot into a mandate. Metaphorically, of course. Founded in 2013, the Mambas have patrolled South Africa’s Kruger National Park to thwart poachers, not with rifles or violence but through constant surveillance, an emphasis on education, and civic outreach. Posted on the Balule Reserve, the 36 members traverse the almost 100,000-acre landmass for three weeks each month to find and eliminate snares, trace poachers’ tracks, listen for gunshots, and report on even a whiff of suspicious activities.

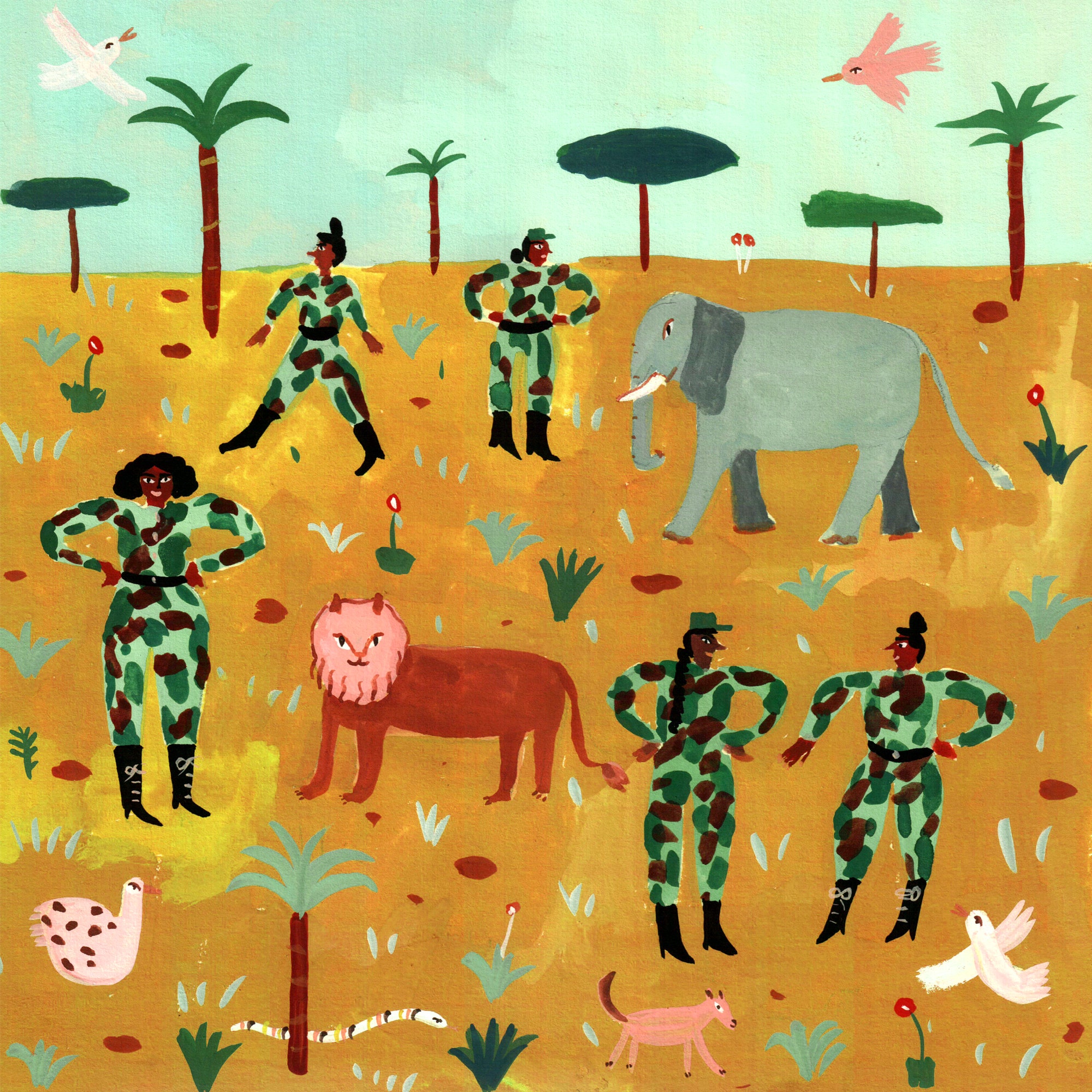

While the women are unarmed, poachers underestimate them at their own risk. Clad in camo-patterned uniforms, badges visible, the Mambas aren’t some PR stunt or a sweet cause; (1). Incidents have decreased by over 70 percent since the Mambas were founded, according to their website. And the women believe the number will continue to fall, thanks to both their skill in the field and their deliberate investment in education.

The women who’ve been recruited into the Black Mambas tend to come from the local communities — the same ones where poachers look to draw villagers into the trade. It’s not that the joiners hate animals; the fact is, opportunities to generate a real income in their neighborhoods are slim. To stress the value of conservation and to push back against the idea that poachers make fast cash, the Mambas introduced “ (2)” lessons to reach kids in schools. “If the Mambas patrol the fence, but their message is not getting into the communities, then they’re fighting a losing battle,” says Lewyn Maefala, who helps run the initiative. “We have to tackle both sides — in the reserve and in the classroom.” Over Skype last year, Maefala schooled me in the Mambas’ environmental efforts, changing perceptions in South Africa, and what makes women better at this work than men.

**Mattie Kahn:** At what point in your life did you realize you were interested in nature?

**Lewyn Maefala:** When I was growing up, I wanted to be a lawyer, but I didn’t have enough money to go to school. So I thought, *If I can’t protect people, I’ll protect nature*. I’ve loved nature since I was young, and I wished that one day I would come and help save wildlife. After he founded Black Mambas, Craig went to villages to recruit new members. I was recruited, I came, and now that’s what I do.

**MK:** I know this is an obvious question, but what do animals need protection from?

**LM:** It’s poachers. Lately, we’re focused on rhinos, since the rate of killing them is so high. People come inside our reserve, looking for rhinos to kill for their horns, which they sell for money. We protect the animals, and we are there to remind the poachers that we are here, and we are watching.

**MK:** When you first decided to join the Black Mambas, what did people think? How supportive are local communities of this work?

**LM:** At first, they thought it was dangerous for me to do this kind of job. “It’s a man’s job!” I just laughed. Now they’re used to it, and they love it, especially because I’m doing it as a woman. I think mostly communities are supportive because they know that what we do is important.

**MK:** Were you scared when you started?

**LM:** At first, I was scared of the animals. The lions are just so, so big. But now we know how they move, what they do, when they will respond, and I’m not scared. It’s our job. We have to be seen as examples — not only in our communities, but the poachers have to know we’re not afraid. We lead by example.

**MK:** The Black Mambas have gotten serious results since 2013, and the numbers just seem to improve. Do you think women are just better at this work than men are?

**LM:** Yes, especially because most of us — we are mothers. And as mothers, we have that instinct to protect our children. Now the animals are our babies, too, and we look after them. It’s a maternal job, I think, and it requires maternal instincts. Women are top-notch, the best, better at this than men. I think it’s because mothers don’t abandon their children, and women don’t abandon these animals. But also, we want our children and grandchildren to be able to come see the animals. I do think women think about the future, maybe more than men.

**MK:** You work specifically on Bush Babies. Why are the Black Mambas so invested in education?

**LM:** If the Mambas patrol the fence every day, but their message is not getting to the communities, then they’re fighting a losing battle. If the Mambas protect the animals, but people in the villages don’t know that we need to keep the wildlife safe, then it’s a losing battle. So we tackle both sides of the problem — the protection and the education about what needs to be protected. That’s why we started the Bush Babies. That way, we can tell kids, “We do not go into the reserve because of this, this, and this.” We offer information back into the communities so that people know what it is the Mambas do on the reserve.

**MK:** Do you find that kids are interested?

**LM:** They’re very much fascinated by the uniform, for one. And they can’t believe the Mambas don’t take rifles into the field. That’s a very new concept for them. They see us as role models and it’s a challenge for them: “Oh, I want to do that as well.” We are people for them to look up to. One of them said to me, “I want to be a beautiful model, but now I’m going to be a teacher too.” So, that was a success!

**MK:** You mentioned that the Mambas’ message needs to reach local communities. Has it?

**LM:** Environmental education is a long-term investment. We can’t say now, “Yes, it’s working,” or “No, it’s not working.” We’ll need to see what the attitudes are to the environment when these children are grown up. But since the Mambas have started, the number of poaching incidents has dropped. That, we know. The reserve lost nineteen rhinos the year before the Mambas started, and since the Mambas started, we’ve only lost six. You can see the drop.

**MK:** You’re optimistic about the work the Black Mambas do, but how worried are you about the environment and the future of conservation in general?

**LM:** I am worried. I’m worried about the future generations; when they look at nature, what will they see? I’m heartbroken to see pictures of the dodo bird, you know? I would have loved to see one in the wild, but it’s impossible because the species has gone extinct. We can only see those birds now through pictures. I don’t want that for the kids. I want children to see the actual animals.

The reason I do conservation is because I want to bring change myself; I don’t want to think that other people will just do it. With Bush Babies, I meet people all the time who don’t know the role of a lion or an impala. They don’t know the roles of these animals, so they don’t understand why we think they are so special. What we can do is teach them that, and that gives me hope.

**MK:** Finally, do you have a favorite animal?

**LM:** I do have a favorite! The porcupine. It fits with me. Just like the porcupine, I’m very relaxed when I’m on my own, but the moment I’m bothered, I take out my quills, and they’re going to hurt. A porcupine tells people, “Don’t mess with me.” We have that in common.

*This interview has been edited and condensed.*

*Mattie Kahn is a writer at elle.com.*

1) (http://www.blackmambas.org/about-us.html)

2) (https://www.nationalgeographic.com/adventure/destinations/africa/south-africa/black-mambas-anti-poaching-wildlife-rhino-team/)

3) (http://www.blackmambas.org/bush-babies.html)