As violent conflict roiled the tiny Southeast Asian nation of Timor-Leste around the turn of the millennium, Christie Warren, a Virginia-based attorney, packed her bags. Warren flew nearly 24 hours from Richmond, Virginia, to Sydney, Australia, and then on to the northern-Australian outpost of Darwin. There, she boarded a United Nations plane north for Dili, Timor-Leste’s capital. She settled into her new living quarters: a cramped container on a barge floating off Dili’s coast, which she shared with a rotating roster of roommates.

Each morning, she walked a gangplank to work in Dili’s municipal buildings, where power and running water had yet to be restored. In 1999, the Timorese had launched an uprising for independence from Indonesian rule. The months of bloodshed would decimate an estimated 70 percent of the local population. Some days, Warren helicoptered over armed militias en route to remote provinces. She returned to the barge each evening before sunset, after which fighting and looting tended to escalate onshore.

The assignment was a typical one for Warren, who has spent decades traveling — often at the behest of the United Nations — to regions reeling from upheaval. She has worked in more than 55 countries, including Iraq and Afghanistan.

Her job: provide support and advice to local leaders as they seek to bolster legal systems and institutions frayed by conflict. That might mean aiding in implementing new criminal codes, or even helping to draft a new state constitution from scratch. In Timor-Leste, it meant establishing a training program for local judges.

“There’s a vacuum that comes immediately after conflict,” Warren tells me. “You have to start thinking about and planning for rule-of-law issues immediately.” A functioning court system where perpetrators are held to account, she says, is a major step toward reestablishing peace.

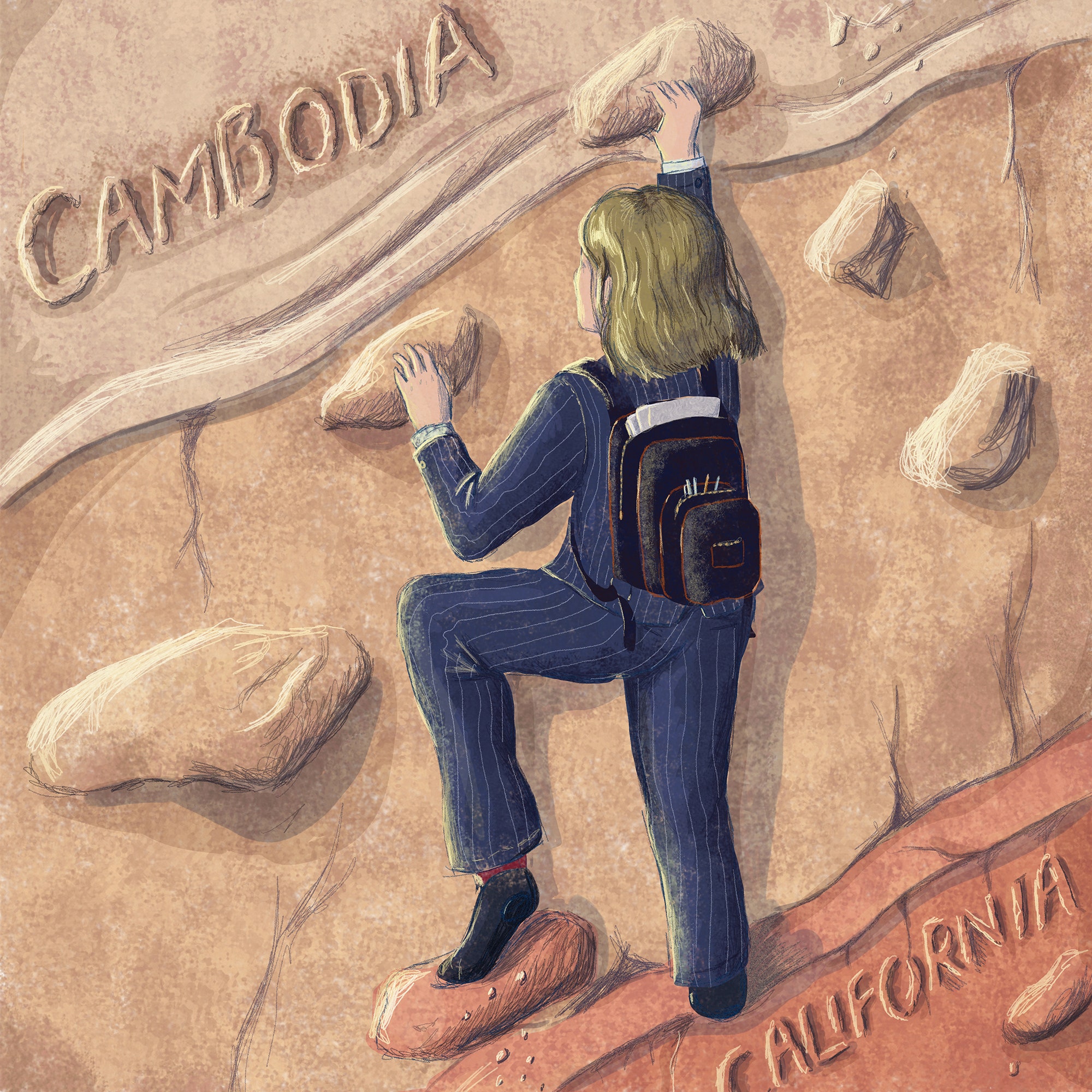

Warren, a Bay Area native, has expressive green-gray eyes and shoulder-length dark-blonde hair. She chuckles often and chats with a warm gregariousness that belies a deep intensity. When she speaks about her work, it’s with a seriousness that makes it easy to imagine her counseling heads of state, or donning a powder-blue bulletproof vest in Iraq, or running marathons and scaling Himalayan peaks—“for fun.”

At the core of Warren’s work is her fundamental belief in the power of comparative analysis — of seeking out a wide array of perspectives and possibilities. She doesn’t presume to tell officials, for instance, how to structure their legal or judicial systems. Instead, she presents them with options that have worked well in similar situations elsewhere. In 2007, in Kosovo, for instance, she created a PowerPoint for local officials with several examples of what an effective decentralized government might look like.

“I don’t like linear thinking, being locked into one perspective,” she says. “I find it to be kind of elitist. I want to know what the other options are.”

In short, Warren is an adviser — not a scribe. And this distinction is a crucial one, she says, particularly given what she characterized as a long, troubling history of Western nations dispatching their own officials to mold constitutions elsewhere to their liking.

“There’s a misconception that international advisers parachute in and tell people how to live a better life,” she says. “The whole idea of Western domination is just kind of an ugly part of our history. It’s not the norm anymore.”

Warren’s comparative approach has also informed her personal decision-making. She told me she didn’t initially set out to broker world peace. Rather, she found her way to her current work by giving herself permission to imagine — and then investigate — alternative pathways.

As an undergraduate at University of California, Berkeley, Warren was drawn to the field of comparative literature because it encouraged pluralist thinking. In the process, she became fluent in French, Spanish, Latin, and Swedish. She seriously considered pursuing graduate studies in the field and teaching full-time. But on a post-graduation backpacking trip through Europe with her then-boyfriend, she changed her mind.

Somewhere between Sweden, France, and Germany, she remembers thinking, *Do I want to spend the rest of my life conjugating verbs?*

Instead, she enrolled in law school at the University of California, Davis, and then worked as a public defender in California, representing defendants who had been charged with a crime and lacked the means to hire a private lawyer. Around that time, she met her husband, Roger Warren, who was then a judge in Sacramento. They married in 1983 and have two grown children. In her nearly seventeen-year criminal-defense practice, she developed special expertise in defending individuals charged with the death penalty, as well as in training other attorneys.

Warren says she might have continued on this track if her hobby of choice, high-altitude mountaineering, hadn’t prompted her to consider a far-flung opportunity. In 1994, Warren was preparing to leave for a trek in Nepal when she heard about a new training program for defense attorneys in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in the wake of a brutal genocide. On a whim, she sent a fax introducing herself and offering to volunteer, since she planned to be roughly in that part of the world.

Some days later came the faxed reply: “Please bring paper, bring pens, bring your friends. We need help.”

She went. Though the fighting had ended years earlier, what she found was gut-wrenching: The Cambodian communist party, known as the Khmer Rouge, had systematically targeted those with a formal education — even individuals who wore glasses or had been seen with a book were suspect, Warren says. As a result, few surviving locals had the training to serve as judges to help maintain peace. So Warren worked for a couple of weeks to train judges and prosecutors, many of whom were respected community elders who had been recruited to the cause.

This, she realized, was the sort of work she wanted to do.

When she returned to California after her volunteer stint, she took a leave of absence (she would later resign) from her job and prepared to return to Cambodia for a longer stretch. Some friends and family members were astounded that she’d trade a comfortable life in Sacramento for the challenges and risks of overseas fieldwork.

For Warren, though, it was an easy choice. As a defense attorney, she says, she might have spent several months arguing on the behalf of a single individual. But through advisory work in the developing world, she felt she could have a broader impact and perhaps help entire populations recover from trauma. During her two-year stay in Cambodia, she arranged a long-distance kid swap with her husband, where first her son, and then her daughter, joined her for about a year each and attended grade school in Phnom Penh.

In the years and countries since, Warren has made it her mission to keep stepping into the vacuum created by conflict and to offer alternatives for order and peace. Lately, she has been advising on amendments to Ukraine’s constitution aimed in part at restructuring the country’s judicial branch and combating corruption in its ranks. She is also a professor at William and Mary Law School, where she is the founding director of the Center for Comparative Legal Studies and Post-Conflict Peacebuilding.

And she continues to climb mountains with a group of close friends, with whom she’s planning an expedition this summer. “I feel like I’ve accomplished something at the end of a trek,” she says. “It brings me peace.”

*Lindsay Gellman is a journalist based in New York. You can follow her on Twitter at (1).*

1) (https://twitter.com/lindsaygellman)