The parking lot at Shrine of the Little Flower church was packed with cars. Everywhere, girls stood around in overalls and tank tops, hugging their parents goodbye and giggling. In less than twenty minutes, we would be boarding one of the yellow school buses lined up against the curb and heading up into the middle of nowhere — the tip of Michigan’s thumb or, as I grew up knowing it, Up North. I was not sure exactly what I was doing there with all those other girls — girls who obviously knew one another from school or church, who seemed excited for the next two weeks, which we would spend doing god knows what. Hiking? Gossiping? Braiding hair?

While all the other families milled around outside, my mother sat in the car with my little sister, Felicia, and me. She rattled off a list of things we should have in our backpacks: soap, swimsuit, socks. I was happy to stay in the car, to not have to mingle in the hot parking lot where the giant statue of Jesus strung upon his crucifix stood tall, watching over everyone. My mother warned us about getting lost or drowning, warned us against poison ivy and poison oak. Right before we boarded the bus, saying our final goodbye, she leaned in close to me and said, “Be careful and look out for your sister. You don’t know these girls.”

On the bus, my sister and I sat pressed next to each other like kittens. When we weren’t watching the girls, we looked out the window, hypnotized by the blur of cornfields and farms and trailer parks that multiplied the farther we drove north. As the sun grew in the sky, the shadows of the fields took on a strange look. Nestled close, my sister fell asleep, but I was awake, a seed of nervousness rooting in my chest.

I was up eavesdropping, taking note of some of the girls’ names and hometowns. There were girls with names I had never heard before — Tegan and Mallory and Lawler — all from places I had never heard of either: Kalamazoo, Orion, Muskegon. I looked at my right hand and wondered where in Michigan those towns could be. With my finger, I jabbed the spot where I lived and wondered if any of the girls had heard of Southfield, or at least driven through it to get to Detroit.

***

It was early evening by the time we got there. Up North, the air smelled different, like seaweed and wet earth just beginning to dry. This was the first time my sister and I had ever been to camp, the first time we had ever entered a forest. A few feet away, sloping down a dirt path, you could see Lake Huron panting, washing across the shore. I looked at it in awe, surprised by its endlessness.

My sister and I wandered around the open dirt driveway, looking for a place to sit, until we were given instructions on where to go. In the distance, we spotted a log where two other girls sat. As we made our way over, I scrunched my face, inspecting them. They were both black — as brown as my sister and I were — and hunched over together, arguing or whispering. I nudged my sister and pointed at them. “That looks like Rachelle, doesn’t it?” The taller girl, hearing her name, looked up, a wide, gap-toothed smile taking over her face.

Felicia and I knew Rachelle and Alana from school and because our mothers had become friends. For a while, we had even lived in the same apartment complex. They stood as we approached, Alana wearing a tiny, pink leopard-print backpack while Rachelle had on a purse in the shape of a cat. In each of their hands, they held small garbage bags instead of luggage. I was relieved to see them, and I wondered if our mothers had planned this or if it was truly a coincidence.

Rachelle and I ended up together in one of the cabins reserved for middle schoolers. We claimed a bunk near the door while the other girls bounded from one to the other, changing their minds again and again, like they were playing some sort of game we didn’t understand. It was easy to spot which girls had been here before — the ones who would always get to spend aimless summers on lakes.

That first night, I did not sleep. I was too awake, too sensitive to the unfamiliarity around me to relax. A few feet away from me, a girl named Amy or Jenny snored happily.

***

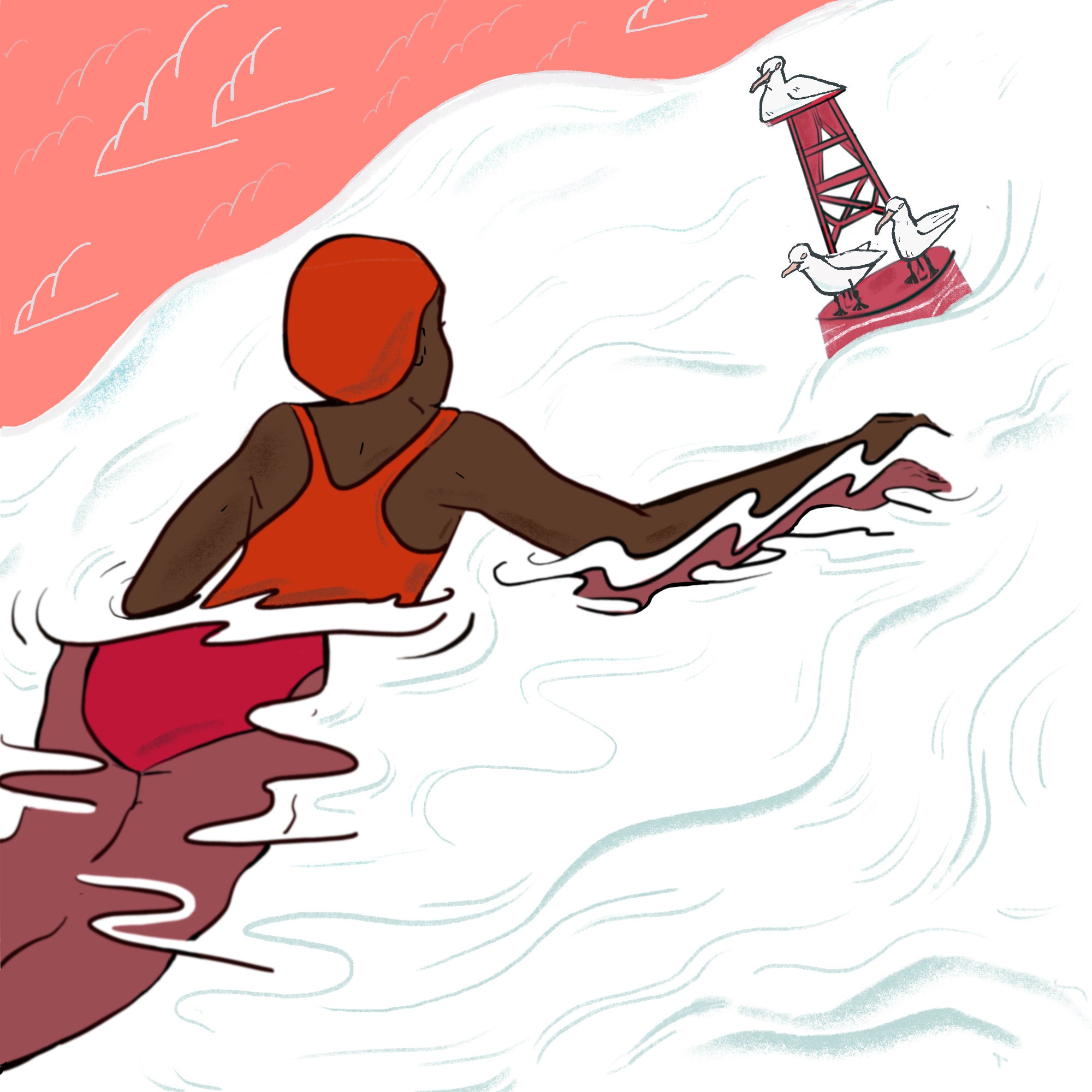

The next morning, Rachelle and I were up early for Polar Bears, one of the activities that we had been encouraged to sign up for. Polar Bears had seemed like the least demanding to me, aside from waking up at dawn. Each morning, we had to meet at the lakefront and swim out to the buoy and back in the freezing water.

That early, it was still blue outside, and things howled and hummed in lullaby. Rachelle and I descended the path that led to the lake, slipping on the slick morning dew. There were four other girls waiting, all of them shivering against the early-morning air. One by one, we were ushered into the lake by a sporty, blonde-haired counselor named Jamie. Once we were in the water, bobbing like baby ducks, Jamie blew hard on her whistle: our signal to start swimming.

|||

The author posing with her camp friends.

|||

The water was playful, sloshing us around on its tiny waves. The buoy marker floated far out in the distance. The waves were hard to navigate, pushing and pulling me back to the place I’d just swum from. So cold that it made my teeth rattle. Back home, Felicia and I had spent most of our summers at the pool, playing for hours while our mother lay in the shade reading. But the pool wasn’t alive like the lake was, and while the other girls burst forward, Rachelle and I floundered. Back on land, I curled into my towel, sandy and embarrassed. Rachelle sat next to me, doodling in the sand. We did not reach the buoy.

The next morning was painful. Rachelle and I complained to each other about our sore bodies, the water that was still lodged in our ears. It was cold, and the forest seemed to reverberate with the embarrassment I still carried.

Back in the water, I lay on my back and looked at the sky. I had always thought I took to the water naturally, but now I was doubtful, heartbroken even. I floated miserably for a bit, ducking under when my face grew hot with memory. A few feet away from me, Rachelle hummed gently to herself, trying to scoop a fallen moth out of the water. If we didn’t go too far out, the water stayed manageable, and we could drift undisturbed. I liked water best this way, friendly and rolling.

Still, something propelled me forward, out to the buoy. After a bit of floating, I began to swim but only made it so far before the water wrapped around me, tugging. There was a divide, a place where the water seemed to turn on me, hurling me back to the shore. Over the sounds of the water, I heard Jamie’s whistle calling us back. My face hurt, slapped raw from the waves. I ducked down under the water and swam back as fast as I could.

***

In the canteen, later, a girl asked me if black people know how to swim. It was a strange hour on the campgrounds, a slow high noon that approached just before lunch. A few girls were there already waiting for the lunch ladies to open the doors to the kitchen. I looked at the girl without speaking. I told her I know how to swim — that my sister and Rachelle and my family all know how to swim. I started bragging about myself, telling her about all the times I’d won a race or done a front flip. *I learned to swim when I was four years old!* But the door to the canteen creaked open, and the girl, no longer interested my answers, darted away. The next time I saw her, she was eating a sandwich, smiling.

At lunch, Rachelle told me she wasn’t coming back to Polar Bears. I didn’t tell her about the girl’s question or her unimpressed gray eyes. When I asked her what she wanted to do instead, she giggled and pulled out a necklace she’d made for her sister, Alana. “Jewelry class,” she said, dangling the beaded necklace in front of me, “You should switch!” I nodded, but something inside of me was burning to make it out to the buoy. Suddenly, I had something to prove, an aching grudge fueling me.

Lake Huron swallowed me whole, pushing me beneath wave after wave before I learned to bob with the tide rather than buck against it like a drowning animal. Each morning, I woke with the sun and made my way to the water. Embarrassment made me diligent, and even when I was not in the water, it still felt like I was pressing myself hard in the direction of the floating marker. Back in the cabin, Rachelle showed me her jewelry — bracelets and earrings made from feathers and stone — and I wished I had left Polar Bears like she had. But I was playing a long game. And every time I looked at the water, I knew I was struggling against myself, against the girl who asked me if I could swim, and with something large that I couldn’t name.

***

On the last day of camp, we got together for a bonfire on the lake. Underneath a full moon, we took communion and recited a prayer as all the girls clasped their hands together around the fire. Rachelle and I mumbled made-up words beneath our breath — those prayers were not the same as ours. In the distance, the lake glittered. The waves were choppier than usual, and I wondered what it would be like to glide between them effortlessly, black like an eel. Rachelle was watching the water too, and after a few seconds of silence, she said, “I didn’t get to swim out here as much as I wanted to.”

On our way back to the cabin, Rachelle and I decided that when we got back home, we would try to get our mothers to take us to Belle Isle. Rachelle always liked it better out there, with the cars and the barbecues and the skylines of Detroit and Windsor. “It’s easier to swim out of that water.”

*Gabrielle Rucker is a fiction writer and essayist. She is a 2016 Kimbilio Fiction Writing Fellow and has been featured in Strolling Series (USA), a short documentary series that aims to connect the scattered and untold stories of the global Black/African diaspora. Her writing has appeared in* Nylon, PINE Magazine, Sunday Kinfolk, mater mea, *and more.*