Two years into his unplanned career as a missionary agronomist, my father wrote to Grandma Lois: *You said not to wear ourselves out taking care of Ti Marcel. I think in a way it’s therapy for me*.

At nine months old, Ti Marcel had neither hair nor teeth and could not sit up. She weighed under eleven pounds. My father brought her home from the pediatric ward so that my sisters and I could shout some life into her, but she didn’t smile or giggle like other babies. Her skeletal arms jutted out from her distended abdomen, and she had wide, unblinking eyes and a rib cage like a shuddering kite frame, ready to catch in the slightest breeze and lift her out of our hands, drifting beyond the horizon, lost to the world.

My little sister Rosie, who was four years old and eager for a younger sibling, leaned in close and tickled Ti Marcel’s feet. I was eight and aware of all the attention I had already lost. I turned away. Her papery skin reeked of scabies medicine and urine.

She had no name. The Haitian nurses at the hospital called her Ti Marcel, little Marcel, and this name — the name of the father who had apparently abandoned her — was one of the few things we knew about her. The fragments of backstory, which we acquired piecemeal from uncertain sources, were as follows: Her mother was said to have died soon after giving birth; unnamed relatives fed her watered-down tea instead of milk, then left her at the missionary hospital. They had not been in contact since that time. Her father, Marcel, was rumored to have fled the country only to be thrown into detention once he arrived in Florida.

It was an old, tired story — yet another survivor with a strong body and shrinking options who had risked everything for a chance at *Peyi Bondye*, God’s Country: where coins could be found on the street, free for the taking; where all the children had enough food to eat and all the fathers had three-car garages; distant realm from whence the missionaries hailed; mythical land of the minimum wage.

***

My father brought Ti Marcel home from the pediatric ward every chance he could find, and took her out in the rain to feel the sharp sting of raindrops on her bare arms. Cradled against his chest, her ungainly head listed awkwardly on a thin neck. In the waning and humid dusk, my sisters and I raced in breathless circles around their two-headed silhouette under the *zanmann* tree, playing freeze tag in the dust.

As the months whirled by, my father’s letters radiated pleasure. Ti Marcel had learned to sit up. She grew hair. She developed a taste for my mother’s home-cooked dinners, mashed into gruel by my doting father. *Baby Marcel is everyone’s example of a miracle*, he boasted to Grandma Lois. *Yesterday she held a bottle all by herself*.

Even I couldn’t deny the transformation. My father had always insisted that she was a smart kid — he could tell by the way her eyes followed us around the room — and within a few short months, she had blossomed into a determined, curious child. She could follow all the prompts in the Pat the Bunny book when she sat on his lap: Lift the handkerchief to play peekaboo, pat the man’s scratchy beard, put her finger through the gold wedding ring.

***

My father adored Ti Marcel. I considered her a menace. I hated how gently he spoon-fed her gulping hunger, as if he would do anything to rescue her. He never seemed exasperated when she soaked the bed with diarrhea, but if I sassed back instead of setting the table like Mom asked, he’d slam open the drawers in the kitchen and yank my arm while paddling mightily with a wooden spoon. Ti Marcel didn’t have the strength to defy him, and no matter how little attention he gave, she turned to him like a sunflower.

Even now, I can remember the texture and shape of my jealousy, wadded up like a loose sock under the heel of my roller skates, grating against my anklebone every time I rounded a corner. Jealousy jarring and black-heat-abrasive, like the skid of sweaty knees and palms on jagged concrete when I hit gravel and my skates flew one way and my arms another — blood from broken palms and a skinned nose leaking into my sobbing mouth. At eight years old, I didn’t care what became of her. I wanted my father back.

***

With only six months to go before my father’s contract at the missionary tree nursery expired, it was unclear what our future might hold. There were no jobs waiting back in the States, and aside from a cabin in the mountains with a pit toilet and pipes that wouldn’t last through a winter, we didn’t have anywhere to live. Thus, when a letter arrived with the news that one of my aunts in California was willing to adopt Ti Marcel so we wouldn’t have to leave her in Haiti, the argument that had been brewing for months spilled out into the open.

My father, swept along by the hope that this borrowed Haitian daughter would soon become a part of the family — even if only as a niece or cousin — wanted to move her out of the pediatric ward permanently. My mother reminded him that Ti Marcel already had a father, even if he hadn’t been able to return for her.

This, at least, was enough to force my father to stop and consider his actions. He drove the next day to Cap-Haïtien to place a collect call to his sister. Shouting over a badly connected line in a sweltering phone booth, my father explained that as fond as he was of Ti Marcel, it didn’t seem right to uproot her from her family. We would just have to trust that God would continue to protect her.

My father continued to pamper Ti Marcel without any hope of permanence, bringing her home every night for dinner, until my sister Meadow and I complained. Even Rosie was tired of playing with her. Couldn’t we do something else for a change? For once, my father relented; that night we played checkers. Meadow, who didn’t appreciate getting skunked by my two kings, tipped over the board. The next night, Ti Marcel was back. She had just gotten her first tooth — which, my father pointed out proudly, hadn’t even made her grumpy — and we celebrated her first birthday with a chocolate cupcake and a candle that we helped extinguish.

***

Exactly one week later, like a character in a mystery novel, Marcel — the rightful father — reappeared. It was an otherwise unremarkable Monday afternoon. Herons squawked in the trees, and missionary kids raced on roller skates around the bumpy circular sidewalk as Marcel, still dusty from his three-hour kamyon ride, made his way in silence to the pediatric ward. He had arrived without fanfare, but he had returned to claim his own.

The prison cell in Miami had apparently been a fabrication. As it turned out, he was a farmer with a small plot of land outside of Gonaïves and he had left his cows and fields for the day to reclaim his daughter. No explanation was given for why, if he owned milk cows, his daughter had been left at the hospital in such a dire condition. The Haitian nurses, bristling with condescension, showed him his transformed little girl, who could now stand against the rail of her crib and bounce with chubby arms. They explained that she had become a favorite of a missionary named *Agwonòm* Jon, who wanted to adopt her.

Marcel’s response was adamant, as the nurses later reported to my father: I don’t want the *blan* to take my baby!

This assertion should have been enough to settle the matter, but by so blatantly demonstrating our affection for Ti Marcel, we had wandered into uncertain territory. Given the historic imbalance of power, it was widely understood that if a *blan* decided to take custody of a Haitian child, his will could not be thwarted, even by the rightful father. Indeed, before Marcel was allowed to take his daughter home, he was sent first to speak with the missionary doctor, who cleared his throat and decreed that the child — for her own protection — was not yet healthy enough to leave the confines of the hospital.

Marcel reiterated to the nurses in the pediatric ward that his daughter would not be raised by a white man, then melted back into the obscurity from whence he came.

My father, who heard about the encounter only after Marcel had left, readied himself for the impending loss. *It seems very right that she should have a real father*, he penned in a letter to his mother later that afternoon. But there was already a catch in his throat — so much so that he added later, as an afterthought scribbled in the margins: *I’m glad she didn’t go today. I will miss her when she does go*.

***

As far as I was concerned, the crisis was over. Now that Ti Marcel had a home waiting for her, I could cuddle her without envy. I wove her hair into soft braids and read her fairy tales on the cicada-humming porch while she sat on my lap and reached for the pages.

Life was looking up again. There were newborn baby bunnies to smuggle from their cages, a kite-day competition at Jericho School, and my new Easter dress, which spun like a gilded teacup when I whirled around the living room. What did it matter that our passports were missing? We were seasoned adventurers by now. The world was full of surprises.

The Limbé Baptist Church celebrated Easter with a long, slow rhythmic march to the river where the baptismal candidates, robed in white, waded into the water singing. The missionaries celebrated with an all-compound potluck.

Ti Marcel sat on my lap while my parents grabbed each other’s waists and barreled across the grass with their legs tied together, taking a noisy first place in the three-legged race. I came in second in the sack races. Meadow, who had just learned to jump rope, whisked around our volunteer cottage, humming to herself. Rosie licked the icing off a pan of cinnamon rolls. Ti Marcel, rechristened Marcelle in my father’s letters, trilled her sweet-voiced gurgle of Da-dada-dah. She had just broken in three new teeth, as sharp as diamonds. She was almost crawling.

***

My mother was up to her elbows in greasy soap bubbles, the bread pans clinking in the sink, when she heard the knock at the door. My father was away at the missionary tree plantation, where he discovered, to his frustration, that the workers were not at their posts, nor even on the peninsula, although they came running as soon as they saw his stoop-shouldered silhouette through the neglected trees. On further investigation, he found hastily scattered branches over tree trunks that he had not authorized the men to cut. He fired them on the spot. Only too late did he learn what he had lost.

My mother felt vaguely irritated as she left the dishes in the sink to respond to yet another interruption. Opening the screen door, she was startled to find Ti Marcel in the arms of a stranger. Marcel, whom we’d never met, explained that he had brought his daughter, Cherylene, to say goodbye.

My mother had just sufficient wherewithal to assemble her own scattered daughters and explain to us that Ti Marcel had a new name and that we might not see her again, then helped us gather up the books and toys and clothes we’d amassed over the previous seven and a half months of pretending that she was our sister.

My sisters and I tagged along as far as the carport to watch Cherylene leave. She seemed happy enough, tucked against her aunt’s hip, her chubby legs showing under her dress as her father, straight-backed and purposeful, strode out the hospital gates.

***

It was just as well I didn’t read my father’s letters until years later.

April 16, 1985 letter to Grandma Lois: *Well my trip went well . . . Sure enough no one was working . . . There’s more to the story but I’m tired and am really writing about something else. When I got back I found out that Ti Marcel was gone. Her father and his sister had come to get her . . . I’m glad I wasn’t here. I would have cried*.

When I opened that letter for the first time, in my twenties, I was surprised at how the dust-winged specter of jealousy fluttered out at me from the page. I had to blink angrily to keep its claws out of my eyes.

Having finally located our missing passports, my father wasn’t about to leave Haiti until he’d seen for himself that Ti Marcel was being properly cared for. Though she had missed her first checkup at the hospital, he and my mother returned pleased from their surveillance mission. Some of Cherylene’s relatives had emigrated to Canada, and the money they sent back helped to pay the living expenses of the rest of the family. Marcel had been tending his gardens a few miles outside of town, but Cherylene stayed during the day with one of her aunts in a well-kept house with cement floors, electricity, and a television — which was more luxury than my father allowed us. She looked cute and healthy and had barely recognized my parents after a month away. She was crawling all over the place and was strong enough to stand and inch along the wall — it wouldn’t be long before she was ready to push off and walk on her own strong legs.

*Rose was so happy to see her. We all were*, my father updated the grandparents.

Two weeks later, we leaned our heads out of the car windows and waved frantic goodbyes as the missionary compound disappeared behind us. A kamyon swerved around us going the opposite direction, the blare of its bugle-call bus horn followed by the clamor of chickens as they fluttered away from the thundering tires. Men on the roof straddled shifting bags of mangoes and manioc, their laughter exploding and then fading to silence as they hurtled past us toward an uncertain future. As we lifted above the runway on a missionary plane, Haiti receded, the dense green thickets of bamboo, Leucaena, and cactus giving way to barren hills. Into one of our going-away cards someone had tucked an unexplained pamphlet: “Are Missionaries Unbalanced?”

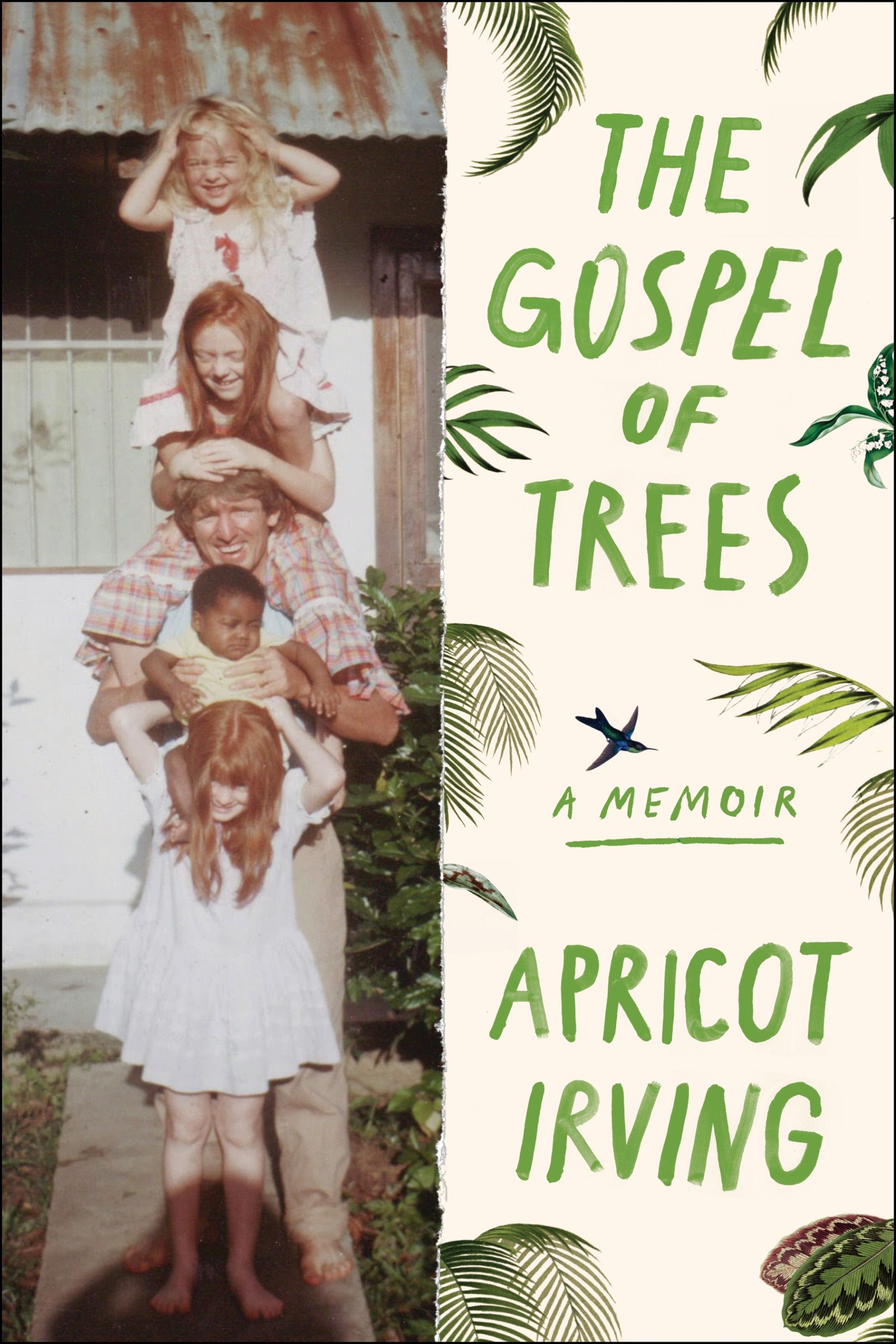

*From* (1) *by Apricot Irving. Copyright © 2018 by Apricot Irving. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc*.

1) (https://www.amazon.com/Gospel-Trees-Memoir-Apricot-Irving/dp/1451690452)